Article and all photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

Where exactly is Monongalia County Ballpark?

Well, obviously it’s in the state of West Virginia, as it’s the new home of the up-and-coming baseball program of the West Virginia University Mountaineers, members of the Big 12 Conference. It’s also where the West Virginia Black Bears of the New York Penn League play their home games. It’s obviously in the county called Monongalia, not to be confused with the river called Monongahela, which flows through the county on its way to fulfill its destiny to create the Ohio River at the tip of Pittsburgh’s downtown triangle. Historians suggest that the county’s name might have been a long-ago misspelling of the river’s name.

| Ballpark Stats |

|

| Team: West Virginia Black Bears of the NY-Penn League |

| Award: BaseballParks.com’s 16th annual Ballpark Of The Year. Read press release here and see photos from the awards ceremony here. |

| First game: by WVU, April 10, 2015; by Black Bears, June 19, 2015, a 15-7 loss to Mahoning Valley |

| Capacity: 3,500, including 2,500 fixed seats |

| Architects: Populous was associate architect and DLA+ was architect of record |

| Construction: Mascaro |

| Price: $22.5 million |

| Home dugout: 1B side |

| Field points: east by northeast |

| Playing surface: Astroturf 3D |

| Betcha didn’t know: Every square inch of the playing field and warning tracks is artificial, except the pitcher’s mound |

Everyone knows that the college town where WVU is located is called Morgantown, so that must be where the new ballpark was built, right?

Nope. “No one would’ve ever dreamed that a small town like ours would be the home of a Mountaineer sports team and a Minor League Baseball team,” observed Patricia Lewis, for a quarter of a century the mayor of tiny Granville, WV. The shiny new park is within the city limits of her town.

How did Monongalia County Ballpark come to be? Was it built to attract a Minor League team? Not at all.

In 2011, WVU was about to join the Big 12 Conference, a conference that takes its baseball very seriously. The Mountaineers had enough of a program to be competitive in the Big East, but certainly not in a “power” conference like the Big 12. The Athletic Director at the time, WVU grad Oliver Luck (a former NFL QB and father of the more accomplished QB named Andrew), knew two major steps had to be taken: replace rickety Hawley Field that the baseball team had used for over four decades; hire a coach who could get the Mountaineers ready for prime time. The coach was TCU assistant Randy Mazey, who instantly provided WVU with a recruiting pipeline to the baseball-rich Lone Star State.

The ballpark was a thornier matter.

Because it would be several years before WVU would receive a full share of conference revenue from the Big 12, Luck used his celebrity status and keen political skills (he’d once run for Congress in the district that included Morgantown) to work with the State Legislature and the Monongalia County Commission on a deal to make a new ballpark a reality. “Oliver Luck deserves so much credit,” Tom Bloom, Monongalia County Commissioner, told me. “He said, ‘OK, let’s work together because (the idea) only makes sense.’ The result is that it’s a community park, and that’s what’s so nice.”

A number of pieces came together, including the the issuance of bonds by the University, the County designating a Tax Increment Financing district, approval of that district by the State Legislature in a special session and a showy ceremony during a WVU baseball game in April of 2013 where West Virginia’s governor Earl Ray Tomblin signed the bill into law.

“The project was delivered under West Virginia’s Design Build Law, so it’s a very prescriptive process,” explained Chris Haupt of Pittsburgh’s DLA+ Architecture and Interior Design, the architects of record on the ballpark. WVU and Monongalia County had to name a firm to handle the bid process so a design-build team could be chosen. Several groups submitted bids, but the team of Mascaro (for construction), Populous (to create the initial designs) and DLA+ (to refine the design into a form that could be built) won the bidding process. Don’t underestimate the role of Populous in this. As we will see in The Interior section below, their vision for the park’s look had a huge impact on the wonderful way it turned out.

| Out with the old |

|

| When the team was in Jamestown, they played at Russell E. Diethrick Jr. Park, built in 1941 (above). Hawley Field (below) was WVU’s home through 2014. |

|

With enough design work done to start construction, groundbreaking took place on October 17, 2013. The ensuing work delivered a facility that could easily accommodate twice as many fans as Hawley Field — with ten times the amenities — but how did pro baseball arrive in the picture?

“The first step was that the University contacted Minor League Baseball, expressing an interest in having a pro team share the ballpark with them,” explained Matt Drayer, General Manager of the Black Bears. “They made the appeal directly to the office of Pat O’Connor (President of Minor League Baseball). From there, it went to the New York-Penn League office, and they took it up with their Board of Directors.” Essentially, the member teams were asked if any were interested in relocating to WVU’s about-to-be-built park. Before a team even committed to do so, O’Connor came to Morgantown and in a press conference, announced that a NY-Penn League team would be coming to town.

The owners of the Jamestown Jammers, Rich Baseball, then expressed an interest in exploring the move. Drayer was the GM of the Jammers, and when he heard that it was likely that a move was in the works, he had mixed emotions. “It was bittersweet for me. I’m a Jamestown native, and being able to operate a team in my hometown was fantastic. But because of the size of that market and the way it had changed over the years, the owners said it was time to make the change. But when I heard that the destination was going to be Morgantown, it was a delightful surprise, because Morgantown was like my second home because I got my undergrad degree there (from WVU).

“If we had to move anywhere in the country, I was glad it was Morgantown,” he added. “And so far, it’s been fantastic here. We’ve sold over 1,100 season tickets and the demand is there. There is a very positive sports culture here, as everyone loves their Mountaineers, and they love their Pittsburgh sports teams. To bring a Pirates (farm) team here to this thriving economic area has been just great. One thing I keep hearing from the folks here is that they are really looking forward to having something to do in the summer. You know, they have WVU football, then WVU basketball, then WVU baseball, and then there was a gap before football started again.” I can’t think of anything better than pro baseball to fill that gap.

| Unsung hero |

|

| No one knows the local baseball scene like Ernie Galusky. He’s coached American Legion ball and assisted at WVU. He’s an entertaining color commentator on WVU and high school broadcasts. And now he’s the Black Bears’ Assistant GM in charge of stadium ops. He was very instrumental in getting the new park ready both for WVU and the pro team. From mowing the berms to coordinating the fireworks, he does it all. |

Although State College, PA wasn’t the first place where a college team shared a shiny new park with a short-season pro team, it’s the place that established how to do it perfectly. There, the Penn State Nittany Lions use Medlar Field through the spring, and then the State College Spikes of the NY-Penn League take over during the summer months. Most would agree that the advent of the first-class facility helped elevate PSU’s baseball program. WVU is confident Mon Country Ballpark will do the same for them.

And the fact that the NY-Penn League schedule doesn’t begin until mid-June makes it a perfect fit for a college facility. “In the League, State College isn’t the only place where they have both,” Drayer pointed out. “Lowell and Vermont also share their fields with colleges, but when you look at Penn State with their big-time athletic program, if it can work there, then having a college and a short-season pro team together can work anywhere.”

Medlar Field and Mon Country Ballpark share more than just their dual purpose. Haupt was the Principal in charge of the Mon County project, and a decade earlier, he was the lead architect for Penn State’s park. He explained that Mon County Ballpark “reminds me a lot of Penn State’s Medlar Field. There’s the view of Mount Nittany. We were building into a hillside. There are a lot of similarities in the projects.”

Drayer points out that Penn State’s baseball facility cost over $40 million, while WVU’s only cost $22.5 million to build. “I think WVU got an awful lot for their money.”

A name-the-team contest was held, since “Jammers” worked a lot better in Jamestown than it would in West Virginia. The name Black Bears won, which is a good one, since these fine creatures do indeed roam the hills of the state, plus no other Minor League team was already using the name. But there is the issue of the geographic designation, as “West Virginia” was already in use by the South Atlantic League’s franchise 150 miles south in Charleston. They are the West Virginia Power.

| The hardware |

|

| Here’s the plaque the Black Bears won for playing in our 2015 Ballpark of the Year. The park beat out three other finalists: First Tennessee Park in Nashville; HoHoKam Stadium in Mesa; and MGM Park in Biloxi. |

Does this make a problem? “I don’t think so, especially since both teams are Pirates affiliates,” Drayer responded. “The way we look at it, we’re drawing fans from a lot of areas (including) Monongalia County obviously, Harrison County, Marion County, Preston County. We look at our market as being regional.” He also pointed out that the highly successful franchise called the Northwest Arkansas Naturals doesn’t use a city name, partly because they didn’t want any of the cities there to feel slighted. “We thought about calling ourselves the North Central West Virginia Black Bears, but that would’ve been too much of a mouthful,” he chuckled.

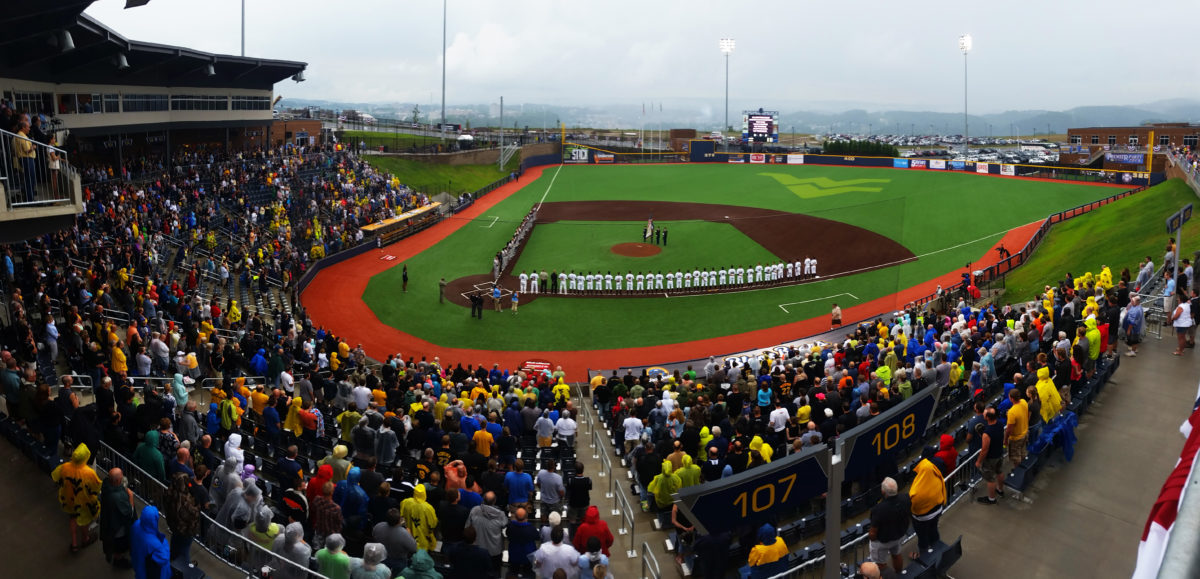

So just two months after the University’s team first used the field, pro baseball took the reigns. The first pitch ever by the West Virginia Black Bears is shown at the top of the second page of this review. It occurred on the rainy, gloomy evening of June 19, 2015.

Amazingly, it appears that the Black Bears are the first affiliated Minor League Baseball team ever to play in the Morgantown area (according to the exhaustive book Minor League Baseball Standings by Benjamin Barrett Sumner). Their arrival — by any measurement — was quite a success.

And success can be measured by the number of happy fans and, of course, by awards — like the Baseballparks.com Ballpark of the Year for 2015. Check out photos from the plaque-presentation ceremony, held on the field of the park prior to the Black Bears game on August 26.

Read on as we explain all the reasons why Monongalia County Ballpark won this award … like its stunning setting, its attractive exterior, its intimate interior and the polished game-day experience that fans encountered here.

The Setting

Construction started on the ballpark before there was even a street in front of the site. Once the park was nearing completion, the University announced that its street address would be 2040 Gyorko Drive. Jedd Gyorko is a Morgantown native who was an All American shortstop at WVU, and when the park opened, he was a member of the San Diego Padres (later traded to the Cards).

Gyorko Drive can be found on a hillside that overlooks the valley containing the City of Morgantown and WVU. To say the view is breathtaking doesn’t do it justice at all. With the possible exception of Staten Island’s view of New York Harbor and the Manhattan skyline beyond, Mon County Ballpark’s view is the best in the New York Penn League.

|

| This shot was taken near WVU’s football stadium, looking up Patteson Drive. The main structure on the right is the WVU Coliseum, and beyond it are the backs of the stores in the University Town Centre Shopping Center. The reddish-brown building on the far left is the new WVU Healthcare building. Mon County Ballpark is just down the hill from that. You can see the park’s light towers if you look closely. |

As we’ve discussed, the park isn’t exactly located on WVU’s campus or even in the City of Morgantown. It’s in the tiny burg of Granville. The town’s houses are nestled along the banks of the Monongahela River directly down the hill from the ballpark, but the saying “you can’t get there from here” pretty accurately applies the situation, as the steepness of the hillside makes it nearly impossible for a road to go directly from the ballpark down to the town. Instead, you’d have to drive several miles out of your way to go from one to the other.

For years, Granville was a coal town. Miners would go underground at a spot not far from the town’s center. Shafts stretched for miles beneath the very hill where the ballpark now sits. Coal from these mines was loaded onto barges via a tipple that still stands (see pictures below). That tipple, interestingly, is directly across the Monongahela River from WVU’s former ballpark Hawley Field.

|

|

| Here’s your picture postcard of Granville, WV. The two upper shots are of the long-neglected coal tipple that brought coal from out of the hill that now holds Mon County Ballpark down to be (on the right) loaded into coal barges on the muddy Monongahela River. Hawley Field sits on the hill across the river. Lower left is the Granville Post Office with the hill with the commercial development in the background. Lower right is indeed that commercial development along Town Centre Drive heading to the ballpark. |

When Patricia Lewis first became mayor in 1991, Consolidated Coal’s production at the mines there was slowing down. “There was devastation here when they finally closed the mines in the early 1990s,” she recalled. Ever since, “we’ve been trying to revitalize the town, trying to be a small community that can offer families a lot of the things that they’re looking for.” Granville has certainly come through in the area of shopping!

When mining ceased here, developers (particularly Mon-View LLC) eventually acquired the desirable property on the top of the hill. Their vision of luring big-box retailers to the site certainly panned out. Today, you’ll find one of the area’s largest shopping centers. University Town Centre features movie theaters, half a dozen chain restaurants, a hotel, a car dealership, Best Buy, Dicks Sporting Goods, Barnes & Noble, Sam’s, Giant Eagle supermarket, Target and Wal-Mart. In fact, when WVU’s baseball team started using the ballpark, fans had to park in Wal-Mart’s lot and walk down the unfinished street to get to the stadium’s gates. Today, Towne Center Drive is completed down to the park’s entrance and parking lot, and one day it will extend another mile where a new interchange is being constructed on Interstate 79. When that’s complete, the park will be much easier to get to. Until then, there’s only way to get there, and that’s through the congested shopping area.

According to Mayor Lewis, it was Mon-View that first envisioned a ballpark as part of this development. As early as June 2012, they announced their desire to add onto the Town Center shopping center with a ballpark and, on the opposite side of Interstate 79, a sprawling business park. In all, Mon-View envisioned 1,400 acres (much of it within Granville’s city limits) being ripe for development … if Tax Increment Financing (TIF) would be approved for this area. Monongalia County and WVU were certainly on board with the idea, and when the State Legislature approved it all in April of 2013, the ballpark became a certainty.

As the baseball stadium opened, the new stretch of Town Center Drive features several new enterprises either under construction or planned. The Mayor said that she’s been told that another hotel, another car dealer, more restaurants and a mixed-use shopping center are planned, all on the Granville side of I-79. It’s important to note that the space directly in between the ballpark and the edge of the hill is being left open so the park’s view will be maintained. Make no mistake, though, that if a business could build on that spot, they’d have one of the most spectacular views you’ve ever seen. Thanks to the University, Mon-View and Granville for agreeing to keep the space clear.

|

| The shot on the left was taken on the shoulder of the newly paved Town Centre Drive. You can see the roof of the WVU Coliseum in the distance on the left side of the image. On the right part of the image is the ballpark’s large roof. The photo on the right was taken from the parking lot of the WVU Healthcare building. |

The stadium isn’t the only WVU project on that hill. At the crest, just behind the ballpark is a new WVU Healthcare facility, operated by WVU Hospital. Its parking lot is handy for those attending baseball games — and provides a breathtaking view of the ballpark and the valley beyond. The shot below was taken from the lot on the far side of the building.

During the earliest discussions of a ballpark being built in this area, some thought was given to the facility being on the very top of the hill, where WVU Healthcare is now. Good thing that thought never panned out, because the wind typically howls there. There would’ve been as many HRs there as at the Cal League’s Lancaster or High Desert. Instead, the park’s site on the side of the hill reduces the wind. Believe me, it doesn’t eliminate it, but it does keep it under gale force — and sometimes, the wind actually blows in from left field.

|

But in discussing the park’s location, the story begins and ends with the view. Zach Allee, Senior Associate at Populous, was responsible for the first drafts of Mon County Ballpark’s design. Before he put pencil to paper, he visited the hillside. “The site was pretty striking,” he explained. “It was really exciting to get to visit it and the University. The plan was always for the fans to be able to see the University (from the park). It was important to us to make that connection, since the park isn’t actually on the campus.” Indeed, depending on where you are in the park, you can see the massive clam-shell roof of the WVU Coliseum to the left, student housing and college buildings in the center, Morgantown’s downtown toward the right and miles and miles of gorgeous hills in the distance.

“When you see that view, you know exactly where you are,” added Allee.

“People just can’t believe the view,” County Commissioner Bloom told me when I asked him about feedback from his constituents. “I think my wife put it best. She said she’d be more than willing to buy a seat here and just look at the view. It’s one of the most beautiful settings you’ll ever see.”

The Exterior

As you may know, Dodger Stadium was built into a hillside in a natural valley called Chavez Ravine. This created the unusual situation where there really isn’t a ballpark exterior behind home plate. In fact, the only way you can enter the ballpark from behind home is onto the very top level of seats.

Mon County Ballpark is somewhat similar. There is no entry gate directly behind home — or behind first base or down the first-base line. That’s because it’s all hillside there (see the photo below left). The ticket office, as a consequence, is near the entry gate in left field. Interestingly, original plans for the facility called for there to be an entry on the embankment side of the park, as we’ll discuss in a minute.

What you see as you are approaching the ballpark from WVU Healthcare or Wal-Mart is the top of the roof that covers the park’s impressive upper level. This is quite unusual in the ballpark world.

If you already have your tickets, you could enter Gate B (below right. That’s the WVU Healthcare building up on the hill), which is behind third base. It opens into the park near the souvenir store. If you need to visit the ticket windows, you must continue down the hill. By the way, since the park’s perimeter has iron fencing, you can easily look in from the outside.

|

There is a separate building that houses the ticket windows (below left). It is located near the left-field foul pole, and the adjacent Gate A is where most fans enter the park. The building impacts the interior of the park in an unusual way, as we will see.

Beyond RF is a much more significant structure (below right) housing the team facilities. It connects to the ballpark’s main concourse on the upper level. Players, obviously, walk out onto the field from the ground level. There is also an entry way (Gate C) for fans there.

|

Read on as we take a look inside this impressive ballpark.