Article and all photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

LAS VEGAS, NEVADA A major figure in American folklore is Howard Hughes. Because he became so reclusive in his later years, the billionaire is surrounded by intrigue and a sense of mystery.

| Ballpark Stats |

|

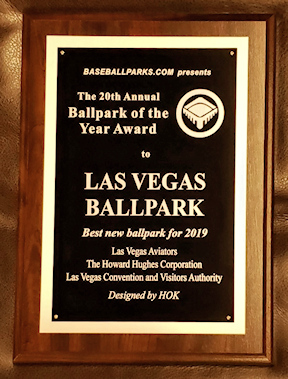

| Award: BaseballParks.com’s 20th Annual Ballpark of the Year — Read the press release here |

| Team: Las Vegas Aviators of the Pacific Coast League |

| First game: April 9, 2019, a 10-2 win over Sacramento |

| Capacity: 10,000, including 8,500 fixed seats, 500-600 on berm and social zone, and 1,000 in the suites, clubs and party decks |

| Dimensions: LF – 340; LCF – 385; CF – 415; RCF – 385; RF – 340. The wall is 15′ tall in LF, 10′ in CF and RF |

| Architects: HOK is Architect of Record. Anton Foss was Principal In Charge and Devin Norton was Project Designer |

| Construction: joint venture of local firm PENTA and national firm Hunt |

| Price: $100 million (estimate) |

| Home dugout: 1B side |

| Field points: Northeast |

| Playing surface: Bandera Hybrid Bermuda Turfgrass |

| Naming rights: The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority paid $80 million for 20 years |

| Ticket info: aviatorslv.com |

| Betcha didn’t know: The ballpark sits on land that Howard Hughes himself purchased in 1952. |

The real-estate-development firm that bears the name of the famous recluse, The Howard Hughes Corporation (stock ticker: HHC), partnered with a group of investors to acquire the Las Vegas 51s of the Pacific Coast League in 2013. There was no intrigue or mystery surrounding the new owners’ intentions, though. It was to move the team out of the worst facility in Triple-A baseball, Cashman Field, into a to-be-built ballpark in an area being developed by the company.

Talk about a fortuitous development for the franchise! Don Logan, who started in sales with the team in 1984 and today is the President and COO, explained that they were so desperate for a new park in the 1990s that they spent five years trying to convince MLB to bring four big-league teams here to conduct spring training. “We thought if we could do that, we could get the kind of ballpark we really need.”

Obviously, that didn’t materialize. The team made attempt after attempt to convince the city to work with them on a new stadium. It wasn’t until HHC came along that things started falling in place.

But even HHC couldn’t make it happen overnight.

It took six years, but the team now has that new stadium. It’s called Las Vegas Ballpark, despite the fact it’s located in the suburb of Summerlin, a planned community developed by HHC. The park carries the Vegas name because the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority (LVCVA) didn’t want the name of the park to fall into the hands of a corporate sponsor or, perhaps, to the development of Summerlin. So in October of 2017, the LVCVA elected to pay $80 million for 20 years of naming rights on the park — a mind-boggling sum for a Minor League facility. The name they chose was Las Vegas Ballpark. The signs on the ballpark incorporate the iconic logo of the City of Las Vegas.

The team went through a name change (thankfully) prior to the 2019 season, dropping “51s” to become the Aviators, a nod to Howard Hughes’ fascination with aircraft. The nickname isn’t the only aspect of the team that sports an aviation tie-in. As we’ll see, so does the team’s logo and, more importantly, the ballpark itself.

When describing the drivers behind the design of the stadium, noted architect Anton Foss of HOK explained that the setting for the facility is “an amazingly beautiful place. There are two elements to that site that spoke to us. One was the terrain, because the Red Rocks are right there (and) the solid earth of the desert. The other was this big, beautiful blue sky. The building speaks to that, in that it’s of the earth and of the sky.”

Structures with that much earth and that much sky don’t come cheap. Because HHC isn’t a governmental entity, they don’t have to divulge how much the land was worth (it was theirs to start with) or what the construction costs were. Sure, it helps enormously that the Convention and Visitors Authority agreed to pay $80 million, but that’s certainly not being paid up front. HHC had to pay for the materials as they were purchased and the labor as the park was being built — and in this area, it’s all union labor, which tends to increase the costs.

But there’s no official word on the costs. I’ve heard estimates that the construction ran in the $80-100 million range, which is believable. The Las Vegas Review-Journal has repeatedly referred to the ballpark as the team’s “new $150 million home.”

We’ll go with a $100 million estimate.

| From the worst to the best? |

|

| The Triple-A franchise in Las Vegas had played in Cashman Field since 1983. When the Nashville Sounds moved out of Greer Stadium into a new park in 2015, Cashman earned the distinction of being the worst ballpark at the top level of the Minors. The move to Las Vegas Ballpark arguably catapulted the team to the top of Triple-A. |

Was it money well-spent? As I’ve researched HHC, I’ve drawn the conclusion that they first seek to do things in the best possibly way, then they worry about what it costs to follow that first-class course of action. This is all on the premise that if they do things right, the return on investment will work itself out. I bounced this hypothesis off an Asset Manager at HHC that I ran into at the park, and he concurred — although he stated that even he didn’t know how much the ballpark cost to build.

Certainly, the early results on the park are exceptionally encouraging. It is getting rave reviews. The team exceeded its goal of season-ticket sales — by a lot. All of the club seats for the season have been sold. The majority of suites have been leased. Celebrity chefs are clamoring to provide input on the menu. Players are commenting that the amenities for them are the best in the Minors.

Sounds like a winner for the Howard Hughes Corporation. Such a winner that Las Vegas Ballpark has won the 20th Annual Baseballparks.com Ballpark of the Year.

But where exactly is this new award winner? What does it cost to attend a game? And very importantly, does the gameday experience match the quality of the facility itself? What would you encounter if you go to an Aviators game?

Read on as we provide all of the reasons why this exceptional facility won our annual honor.

The Setting

So what is Summerlin? Is it a city?

Not exactly. More like a development. Here’s the story, and it’s a fascinating one:

By 1952, Howard Hughes had amassed vast wealth from his dealings in casinos, the aviation industry and movies. That year, he decided to add “land developer” to his long list of titles, so he bought 25,000 desolate acres northwest of the City of Las Vegas.

Aside from the opportunity to create a bedroom community for employees working in downtown Las Vegas, the most interesting aspect of this land had to be that the famous Red Rock geological formations lie just to the west. They are quite visible from most of this property.

When you stand near the front gates of the ballpark and look west on Summerlin Centre Drive, you clearly see the famous Red Rocks. When you stand near the front gates of the ballpark and look west on Summerlin Centre Drive, you clearly see the famous Red Rocks. |

This land remained undeveloped, though, until after Hughes’ death in 1976. It was only then that the concept of a planned community on the property came together. The development’s name was chosen to honor Hughes’ grandmother, Jean Amelia Summerlin. Over the decades, the population within this 25,000 acres grew, until today it is said to top 100,000 spread over two dozen villages.

And to say that the populace here is affluent is a silly understatement, as the average household income is nearly $140,000.

Some of the land is within Las Vegas’ city limits, while the rest is in unincorporated Clark County. The ballpark and its next door neighbor, the City National Arena (official practice facility of the NHL Golden Knights), are in the part of Summerlin that’s not within Las Vegas. Maybe that’s why it was so important for LVCVA to gobble up the naming rights of the ballpark, before it became something like Summerlin Stadium.

The Vegas Golden Knights of the NHL use this as their official practice facility. Its south wall is quite close to the ballpark’s left field fence. The Vegas Golden Knights of the NHL use this as their official practice facility. Its south wall is quite close to the ballpark’s left field fence. |

So the ballpark is on land originally purchased by Howard Hughes himself 67 years before the first baseball game was played here. That in itself is interesting.

Unlike decades ago, Summerlin is well-connected to the rest of the Las Vegas Valley metro area, as Beltway 215 connects the community with population centers to the north of Las Vegas and especially to the south where well-to-do communities like Spring Valley and Henderson are located.

So if you look at a map of the area, you’d conclude that Las Vegas Ballpark isn’t near the center of the two million people who call the valley home. You’d be right — because it’s on the extreme west end of the metro area — but that doesn’t make Summerlin a bad spot for the park.

First, the suburbs on this side of the valley have hundreds of thousands of residents, and they tend to boast very high incomes. Second, the road system makes it easy for folks who don’t live nearby to get there. Third, think about where Cashman Stadium is located. It couldn’t be more in the middle of everything. Yet that didn’t make many people want to go there, as the sorry facility ranked 14th in attendance in the Pacific Coast League in 2018, beating out only two lame-duck franchises, Colorado Springs (which moved to San Antonio this year) and New Orleans (which moves to Wichita in 2020).

And another advantage that Summerlin has over Cashman’s location? Temperature. The gametime temp the last time I was at Cashman was 105. The National Weather Service stated that in the summer, for every 1,000 feet you climb in elevation, the temperature drops five degrees. Cashman sits at 1,995 feet above sea level. The front gate at Las Vegas Ballpark is 3,041 feet. You do the math.

As pretty as any of the casino hotels down on the Vegas Strip is Summerlin’s Red Rock Casino Resort, just two blocks from the Aviators’ park. As pretty as any of the casino hotels down on the Vegas Strip is Summerlin’s Red Rock Casino Resort, just two blocks from the Aviators’ park. |

The ballpark isn’t the only attraction in the commercial area dubbed Downtown Summerlin (yes, developed by Howard Hughes Corporation). Not only is the hockey arena next door, the massive Red Rock Casino Resort — with 830 hotel rooms, gaming and loads of restaurants — is two blocks to the north. And directly across the street is an upscale shopping and restaurant center. It features Dillard’s, Trader Joe’s, Nordstrom Rack, movies, dozens of eateries like Wolfgang Puck Bar & Grill and Maggiano’s — in other words, everything an upwardly mobile community would want nearby. And visitors to a ballpark who want something to eat before a game. And a place to gamble afterwards.

|

| A very short walk from the park’s front gates is the lovely restaurant area of Downtown Summerlin. |

While there’s parking at the casino hotel and shopping center, the main lots for baseball are on the opposite (east) side of the park, by the way. And parking for games is free.

Adding to the convenience of the site is that there is a stop for Regional Transportation Commission (RTC) buses directly in front of the park’s main entryway. RTC operates bus lines all across the Las Vegas metro area.

I find the location for Las Vegas Ballpark to be fascinating, with Beltway 215 a few blocks away and lots of places to eat, shop and gamble within walking distance. Oh, and an up-close visit to Red Rock Canyon is just minutes away. And when HHC finds more entities to lure to the area, there is additional undeveloped land immediately to the south of the park. I’m told, by the way, that the new businesses that are likely to occupy that land will likely be condos and a hotel more than additional entertainment options.

When you consider that Triple-A baseball has come to town, there’s plenty of entertainment already.

Logan emphasized the site’s most important aspect. “Our location is great. We have access to the freeway (and) proximity to the whole valley.”

And with a chuckle he added, “I just wish my parking space was closer. I’m getting in way too good a shape walking up here from my car every day.”

The Exterior

There’s nothing “retro” about the look of this ballpark.

That’s not a criticism. In fact, there’s nothing wrong with a modern look for a baseball facility, as long as it fits in with its surroundings while offering something different.

|

| You can tell two things right away from the main entry: this is anything but a “retro” ballpark; this is something very special. |

When I asked Foss about the look of the park’s exterior, he replied, “The Red Rocks. That’s where the building materials got their inspiration. Everything from the base down, we call ‘of the earth’ materials.”

He explained that the materials used in the lower portion of the exterior are stucco and concrete, “of a color that is like Red Rock, but not really red. It’s more like colors found in Downtown Summerlin, with all of the metal panels and glass that you see there, but executed in a way that fits the ballpark.”

As we’ll see when we examine the park’s interior, the sleek look of an airplane was never far from the designers’ minds. That’s why you don’t see protrusions or sharp corners anywhere on the exterior. “We had this whole ‘aviators’ theme in the back of our minds due to the connection with Howard Hughes’ aviation legacy,” Foss continued. “It lent some consistency to the architecture.

“The building’s steel is mostly gray and black, and then we have this really nice hot color of orange on the undersides of the roof, which is of the Red Rock and of the logo of the Aviators.” Hands down, the orange accents are one of my favorite elements of the park.

|

| The orange accents are in a number of spots, particularly on the underside of virtually every roof. “The design (of the park) was good,” noted Foss, “but it was a little like a ‘symphony in gray.’ We needed a pop of color, so we came up with that orange.” |

The orange underside of the park’s various roofs is mesmerizing, and very fitting for the team’s aviation theme. The first photo above shows the exterior behind the first base on-deck circle. Notice that there’s no wall, just fencing. It’s one of the many ways that air flow is maximized inside.

The other shot shows stairs leading to the main concourse, which is about 17 feet above the street on the east (downhill) end of the site. This building, by the way, is a separate structure from the ballpark. It contains the receiving bays for large trucks below the impressive food-prep facilities.

|

| This gives you an idea of the use of contrasting colors and building materials, all to blend in with the rest of Downtown Summerlin. The landscaping does as well. |

The stairway next to the food-prep building is right by the spot above, the intersection of Oval Park Drive and (this is really a great name) Spruce Goose Street. If you don’t know what the Spruce Goose was and why it would be important to a team called the Aviators and the Howard Hughes Corporation, please Google it! This also gives you an idea of the pronounced slope from west to east on the site.

|

| This is the entry gate in center field, near the main parking lots. |

The most stunning look of the exterior is behind home plate and 1B, on the west and south sides of the park. Since the main parking lots are on the east side, there is a ticket window and entry gate there (above), as well as the really distinctive ballpark logo.

If you’re wondering about the northern exterior, well, there really isn’t one. The southern wall of the hockey arena is almost right on top of the property line with the park, leaving no need for fancy ornamentation on that side of the exterior of the stadium.

Let’s now take a look inside the groundbreaking baseball park, and check out a gameday experience that’s just about perfect — except for one thing.