Back to page 1

WHAT THEY HAD TO SAY

I encountered so many interesting folks while I was covering the events at Rickwood Field — people overseeing the preservation of Rickwood, players, fans who traveled long distances (and paid big bucks!) to attend the MLB game, a U.S. Senator … even the grandsons of the man responsible for building the park in 1910.

Here are some of their wonderful comments …

Bob Woodward, grandson of Rick Woodward

Bob Woodward, grandson of Rick Woodward

Rick Woodward’s grandson Bob (see photo) was three years old when Rick died in 1952. “He’s buried in Elmwood Cemetery, just a couple of miles from here,” Bob says while attending the MLB game on June 20, 2024. When asked what his grandfather would think about a big-league contest coming to the park he’s responsible for, Bob says “He’d be thrilled to death.”

Obviously, Rick lived his whole life during the time of strict segregation in the South. Asked how his grandfather would’ve felt with integrated teams playing in his park, Bob says, “I don’t think he’d care one way or the other. But had he lived long enough (to see the integration of the sport), he’d have been ecstatic.”

Rick Woodward III, the other grandson of Rick Woodward

“I think that Grandpa would be absolutely delighted with the Rickwood events this week.”

Regarding the fact that Major League Baseball has arrived at Rickwood after 114 years, he says “It is a perpetuation of his dream. Remember that Rickwood was structurally designed to add a second deck of seats a la the Major League stadiums of his era.”

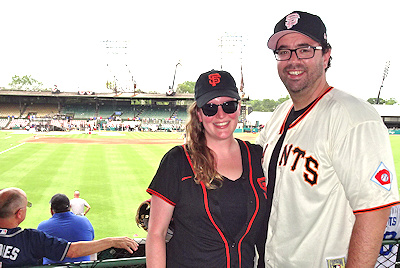

Jake Flynn, Giants fan living in Los Angeles

Jake Flynn, Giants fan living in Los Angeles

Flynn crossed the country with his fiancée Emily Kurbin (see photo) to attend the events at Rickwood. But it wasn’t just to see his favorite team play.

He calls himself a fourth generation Giants fan. “Both of my parents were raised in the Bay area, so I grew up going to Candlestick Park and Pac Bell.” What drew him to Alabama, though, is that “this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The second I heard it was going to happen, I didn’t feel I had a choice. I had to come.”

He’s glad he did. “It’s hard not being emotional walking around here.”

Gerald Watkins, chairman of the board of the Friends of Rickwood

Gerald Watkins, chairman of the board of the Friends of Rickwood

I had conducted a long interview with Watkins on the phone as I was preparing preview articles about the Rickwood events. It was nice to meet him finally on the day of the big game. He posed for a picture with me in the room designated The Rickwood Museum at the ballpark.

When I interviewed him for my preview articles, he gushed about the wonderful renovations made to the ballpark he’s committed to preserving. For one thing, he’s overjoyed with the “brand new baseball surface on America’s oldest park. We’re happy because the Friends of Rickwood have been working for a long time to try to preserve the park and keep it open.

“We have a full slate of games each year that includes travel ball, college ball, high school ball. So we have a list of things that we do. Now, all those folks are going to come into the ballpark and they’re going to see it refurbished and they’re going to think they’ve died and gone to heaven.”

Honestly, if heaven looks a lot like Rickwood Field, I’ll be eternally pleased.

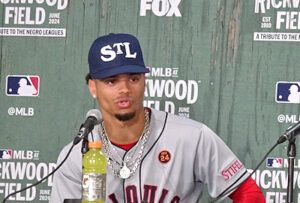

Masyn Winn, shortstop of the St. Louis Cardinals

Masyn Winn, shortstop of the St. Louis Cardinals

Winn was one of only a handful of Black players on the big-league teams in this game. At a pre-game press conference, he said, “Being on the same field as so many historic people, so many legends, it’s pretty special. I grew up learning about these guys. Just to be able to say I played on the same field, I’m going to be able to tell my grandkids that. It’s super important for me.”

When a reporter asked him why he thought there were so few Blacks in pro baseball, he remarked, “Obviously, this field was home to some of the greats in the Negro Leagues. For me, there’s not a lot of brothers in baseball. It’s important to be an inspiration not only for kids around St. Louis, but all over the world, trying to get some color into baseball. I think it would be good for the game.

“I think a lot of kids grow up wanting to be football or basketball players, but they don’t know how fun baseball can be, and how impactful we can be on the field.

“It’s our job to go out there and show the kids that it’s fun to play baseball and compete at the highest level.

“It’s hard not to love this game.” That might be the sentence of the year!

Katie Britt, U.S. Senator from Alabama

Katie Britt, U.S. Senator from Alabama

Due to the friend of a friend, I had the opportunity to interview Senator Britt. She’d come to Birmingham to witness the big events at Rickwood.

I asked her how she felt about MLB bringing this event to her state. ““Alabama has played an important role in baseball. Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron all were born here. We’re so proud to showcase and celebrate these and other men who played here.”

She spoke glowingly of the way Mays approached the game with “exuberance,” a quality often absent in today’s baseball. “That’s what defined Mays as a player.”

Here’s how she sums up her experience of getting to attend these events that honor the Negro Leagues: “It’s just a feeling you get when walking around this park. These men played American’s pastime, and we’re so proud to honor their legacy.”

And while I’d never admit this in a USA TODAY article (for obvious reasons), I found her to be an absolute delight. I can see why she is so popular among her fellow Alabamans.

Don Baker, Amory, Mississippi

Don Baker, Amory, Mississippi

Baker considers himself a lifelong Cardinals fan. Hence the two-hour drive to see his team play the Giants.

“I have a picture of me in a Cardinals shirt when I was a little boy.

“My grandfather had a dairy farm and I’d be in the milking parlor with him when I was five, six, seven. This was the mid-1960s. We’d always listen to Jack Buck doing the Cardinals games on the radio.

“I had to be careful and listen to know when to be quiet so he could hear the game.”

Bob Kendrick, President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Bob Kendrick, President of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

I had conducted phone interviews with Kendrick a number of times for articles I was writing (about MLB’s Inner City Academy program, for Hinchliffe Stadium and for MLB coming to Rickwood), but I’d never gotten to meet him face-to-face. Until the day of the MLB game at Rickwood, that is.

So I asked him if he ever thought this day would finally arrive. He responded, “I remained always hopeful that this day would come.” When I asked him his feelings on this day, he said, “So proud. So proud.

“Any of us charged with being the stewards of the history of the Negro Leagues can’t help but feel a sense of pride about this.”

He then related a story quite poignant to this day. “I once asked the great Buck O’Neil why it was so important to him for there to be a Negro Leagues Museum. He told me, ‘So we would be remembered.'”

As Kendrick watched wheelchair after wheelchair of aging Negro League veterans being wheeled toward the playing field for the ceremony to honor them, he added, “I think Buck couldn’t have imagined something like this happening.”

Tim Whitt, author of “Bases Loaded with History, The Story of Rickwood Field, America’s Oldest Ballpark”

Tim Whitt, author of “Bases Loaded with History, The Story of Rickwood Field, America’s Oldest Ballpark”

I stumbled across Whitt’s book when I first visited Rickwood in the winter of 2000. They had some t-shirts and books for sale in a little store there, and this book jumped out at me. In the quarter century since, I’ve read and re-read this wonderful book repeatedly. I’m being completely truthful when I say that it is one of my favorite books of all time. I put it alongside “Lost Ballparks” by Lawrence Ritter (may he rest in peace).

So when I finally got to meet Whitt at a Montgomery Biscuits game the night before Rickwood’s big-league contest (he’s on the far right in the photo, with architect extraordinaire Jason Michael Ford in between), I was like a little kid meeting his boyhood idol.

When I asked him what it meant to him to have the ballpark he loves host the Cards and Giants, he told me, “I keep thinking about James Earl Jones’ speech in Field Of Dreams. Rickwood showed us what was good about baseball — and can be again.”

Brian LoPinto, Co-Founder of the Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium

Brian LoPinto, Co-Founder of the Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium

There are very few ballparks left that hosted a regular Negro League franchise. Rickwood and Hinchliffe Stadium in Paterson, New Jersey are on that very short list.

I met LoPinto when I reviewed Hinchliffe last summer. I found him to be both learned and fascinating, and I gained much insight about Hinchliffe from him.

I was happy to meet up with him at Rickwood (see the photo of us in the merch tent), and hear his observations about the events, and how appropriate it would be for Major League Baseball to do something similar in Paterson. “MLB at Rickwood Field is a pilgrimage, and I am grateful to have witnessed this moment in history. Rickwood is the Holy Grail of Negro Leagues baseball. Words cannot describe what an MLB at Hinchliffe Stadium event would feel like. Hinchliffe Stadium birthed two Hall of Fame careers as both Monte Irvin and Larry Doby tried out for the Negro Leagues at Hinchliffe.

“Those of us that truly care and have advocated for Hinchliffe Stadium know that patience is a virtue. Major League Baseball will make a decision on Hinchliffe Stadium when the time is right.”

Truly, I hope it happens in the next couple of years.

+ + + +

And there’s no truth to the rumor that I interviewed Branch Rickey for this article, but he once said something about signing Jackie Robinson in 1945 that is quite relevant to MLB’s decision to play this game at Rickwood Field: “If you see a wrong and make an effort to correct it, you shouldn’t seek recognition for doing so.”

For far, far too long, MLB hadn’t done enough to honor the Negro Leagues. This game is taking a step to correct that wrong.

THE TEN THINGS I LEARNED FROM MLB AT RICKWOOD

Much of this appeared in USA TODAY Sports Weekly and on USATODAY.com. Used by permission.

BIRMINGHAM, Alabama “I remained always hopeful that this day would come.”

This is the way the president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Bob Kendrick, summed up his feelings as he watched wheelchair after wheelchair head toward foul territory at Rickwood Field. Each was carrying an aging veteran of the Negro Leagues so they could be honored at Major League Baseball’s much-anticipated event.

Dubbed “MLB at Rickwood,” the three-day event culminated Thursday night in the first regular-season big-league game in the state of Alabama. The marquee said it was the St. Louis Cardinals playing the San Francisco Giants, but the real star was the Negro Leagues. And in particular, the late Willie Mays, who passed away as the three-day event was starting Tuesday, was at center stage. There was even the last-minute addition of Mays’ #24 on the playing field behind home plate.

Dubbed “MLB at Rickwood,” the three-day event culminated Thursday night in the first regular-season big-league game in the state of Alabama. The marquee said it was the St. Louis Cardinals playing the San Francisco Giants, but the real star was the Negro Leagues. And in particular, the late Willie Mays, who passed away as the three-day event was starting Tuesday, was at center stage. There was even the last-minute addition of Mays’ #24 on the playing field behind home plate.

Mays, who grew up just two miles from Rickwood, started his career by playing for the Birmingham Black Barons while a high school junior. He soon became their starting center fielder and led them to the Negro American League title in 1948. In 1950, three years after Jackie Robinson made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the New York Giants signed Mays away from the Black Barons.

The result was a Hall of Fame career. You can make a convincing case that he was the greatest player in the history of the game. Certainly, no one exceeded him when it came to tools.

And it all started here at Rickwood Field.

And now MLB was making a long-overdue visit to honor Mays and the rest of the players of the Negro Leagues – some of whom followed Robinson and Mays into “white” baseball … but most of whom never had the chance.

“Any of us charged with being the stewards of the history of the Negro Leagues can’t help but feel a sense of pride about this,” Kendricks added. “So proud. So proud.”

While it’s obvious that this was largely about the Negro Leagues, we shouldn’t forget what a big deal this is for citizens of Alabama. U.S. Senator Katie Britt (photo) told USA TODAY Sports that her state is justly proud to host this game. “Alabama has played an important role in baseball. Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron all were born here. We’re so proud to showcase these and other men who played here.”

While it’s obvious that this was largely about the Negro Leagues, we shouldn’t forget what a big deal this is for citizens of Alabama. U.S. Senator Katie Britt (photo) told USA TODAY Sports that her state is justly proud to host this game. “Alabama has played an important role in baseball. Satchel Paige, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron all were born here. We’re so proud to showcase these and other men who played here.”

At the end of the evening, the scoreboard told us that Mays’ Giants had fallen to the Cardinals 6-5. But the real winners were the players of the Negro Leagues, as they were honored for their unmistakable contribution to our National Pastime.

Here now are the ten best things I learned while attending the three-day event in Birmingham.

- The impact of the death of Willie Mays

When the PA announcer read the solemn news of Mays’ passing during the 8th inning of the Minor League game at Rickwood Tuesday night, there was stunned silence by the crowd. Slowly a rousing cheer arose from the attendees. It grew into a standing ovation, clearly the loudest the crowd had been all evening.

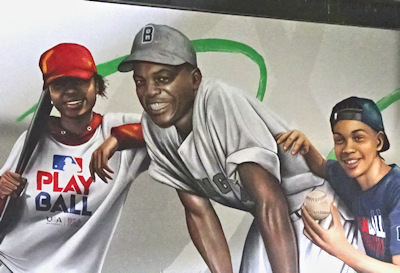

Mays isn’t just the most gifted five-tool player of all time. This is his hometown. On Wednesday, a ceremony was held to dedicate a mammoth mural of Mays in downtown Birmingham (see above). He is revered here, as he should be.

Rickwood Field has gone by the same name since it opened its gates. I’m sure there would be a groundswell of support for the first renaming of the ballpark in its 114-year history. How about “Rickwood Field at Willie Mays Ballpark”?

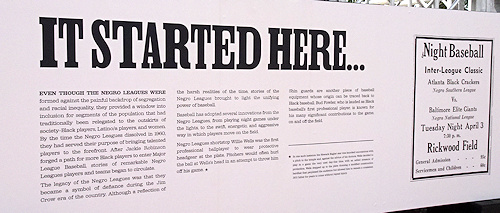

- Honoring the Negro Leagues shouldn’t be a one-time occurrence

There were two homers in the game, the first by the Cards’ Brendan Donovan, who grew up in Alabama, and the other by the Giants’ Heliot Ramos. Both landed beyond the right field wall.

This is the spot where bleachers once stood at Rickwood. Those uncovered bleachers (remember most games were played during the day, and Alabama’s blazing sun cooked the fans there) were “colored only” during the days of segregation in the South.

Those bleachers are gone, as is segregation. But the lessons of that time need to be remembered.

That’s why this game honoring the Negro Leagues shouldn’t be a one-off occurrence. Now that there is a brand-new multi-million-dollar playing surface and the heavy lifting of figuring how to pull this off has been perfected, it’s time to make this an annual event.

But there are so few parks left standing that once hosted Negro League ball, MLB should make the effort to bring a “jewel” event like this to them. Those include Paterson, New Jersey’s Hinchliffe Stadium and Hamtramck Stadium in Michigan. Even if they simply can’t accommodate a full-fledged big-league game, bring a Minor League game or a charity game with former players.

MLB, please do something at these aging parks while these treasures are still here.

- MLB has learned from each jewel event

The family tree of this kind of jewel event traces its roots to 2016, when MLB constructed a temporary ballpark on an abandoned golf course at Fort Liberty (called Fort Bragg at the time) in North Carolina. Since then, MLB has rebuilt a tiny Minor League park in Williamsport so a game could coincide with the Little League World Series, and created a temporary stadium in the cornfield in Iowa where the “Field of Dreams” movie was filmed.

Each created tremendous buzz and generated very positive press for MLB. And each outdid the previous event in the scope of fan amenities.

The facilities for this week’s events in Birmingham truly top any previous such event. And it’s not close.

MLB brought more food stands, more port-a-potties, more merchandise trailers, a bigger stage for music acts, more first-aid stations, more misters, more beer stands and more room for fans to mill about.

And all of that is outside of the ballpark. This is a tremendously impressive operation.

- The logistics to pull this event off were mind-blowing

And to pull all of this off, it took a monumental throng of support people. Counting ground crews, production folks, broadcasters, ushers, security, vendors, and more, there were more than 2,000 people involved – for a game with an attendance of only 8,332.

Just like the facilities, this was truly impressive. And even more impressive was MLB’s commitment to hire locals for the majority of the positions. Well done!

- The contrasts were striking between a modern-day game versus how baseball was played a century ago

When a modern-day big-league game is brought to a facility this old, it’s fascinating to see the stark differences between facilities of today versus a hundred years ago.

Today, players must have spacious, air-conditioned clubhouses, versus the hot, cramped locker rooms of yesteryear (which are still here in case you want to inspect them). Fans expect high-resolution video boards, although the hand-operated scoreboard in left field is still in use. The lighting of today has to be tremendously better, although the rickety old light standards are still here, but aren’t used (and in fact don’t have the bulbs in them to protect the players in case a foul ball hits them).

And the playing surface had to be completely dug up and replaced.

MLB made sure the players and fans had everything they needed for MLB at Rickwood.

6. This was a paradise for souvenir collectors

There were at least four different points of sale for merchandise, and the offerings were different at each. Collectors had a field day with Rickwood pennants, posters, books, pins and so much more.

And even though there was some lovely memorabilia that wasn’t for sale – including Willie Mays’ plaque from Cooperstown (below) — everything was still displayed beautifully. Their historic value is obvious.

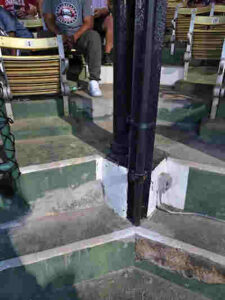

- The planners used a “gentle touch” in getting Rickwood ready for MLB

Rickwood Field is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. That means you can’t really gut it and start over.

Rickwood Field is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. That means you can’t really gut it and start over.

Although that would have been easier.

MLB’s approach was to maintain the character of the historic facility – and that meant that cracks in the pavement and decidedly uneven steps remained (see photo). There were well-trained ushers at every such point to help fans up and down these troublesome stairs safely, though.

MLB made the changes they had to — lights, field, dugouts, etc. — while leaving much of it alone.

“The goal was to take a very gentle touch to it,” says Todd Barnes of Populous, the firm tasked with planning the logistics of pulling off this herculean project. Perfectly done!

- Adult Major Leaguers can be like little kids

It’s always enjoyable watching grown-up, professional players come to events like this. They are giddy like little kids.

About playing in the same place as Aaron, Robinson and especially Mays, Cardinals shortstop Masyn Winn noted “It’s pretty special. I grew up learning about these guys. Just to be able to say I played on the same field, I’m going to be able to tell my grandkids that. It’s super important for me.”

He also acknowledged that Black players like him need to promote the game so the next generation will want to play baseball instead of other sports. “It’s our job to go out there and show the kids that it’s fun to play baseball and compete at the highest level.

“It’s hard not to love this game.”

- MLB created a four-day entertainment event, rather than merely a single game

When MLB staged the game at Fort Bragg, it was basically a five-hour event. Soldiers arrived, enjoyed the game, and went back to their barracks.

Since then, this type of jewel event has grown into an extravaganza.

Since then, this type of jewel event has grown into an extravaganza.

In Birmingham, Monday had a special screening of a movie about Mays. Tuesday had Minor League teams battle it out at Rickwood, wearing Negro League uniforms. Wednesday had the mural dedication, concerts and a celebrity softball game — all celebrating Juneteenth. Thursday had a day-long series of remembrances and fun. The musical performances before (Jon Batiste delivered an A++ performance) and during the game were next-level. Overall, the pre-game ceremonies were, in my opinion, the best the sport has ever seen. It reached a crescendo with a thrilling fly-over (above).

And, oh yeah, there was an edge-of-your-seat, one-run baseball game.

All around town, MLB was hosting charity events, skills workshops for kids, watch parties and luncheons. It was a dizzying schedule. And one that served the people of Birmingham extremely well.

- Baseball is fun

True, the announcement of the passing of Willie Mays added a somber air to the proceedings here, but it was still evident that baseball is a fun game. If this event doesn’t rekindle your love of the sport, I’m not sure anything can.

True, the announcement of the passing of Willie Mays added a somber air to the proceedings here, but it was still evident that baseball is a fun game. If this event doesn’t rekindle your love of the sport, I’m not sure anything can.

MLB at Rickwood also reminds us that Negro League players felt they were entertainers as well as athletes. There is a huge banner of first baseman Richard King along the first-base side of the ballpark (see photo). Known as King Tut, he played for the Indianapolis Clowns. And true to his team’s nickname, he was famous for his comedic antics on the field.

Senator Britt of Alabama chose the perfect word to describe the way Mays approached the game. She said he played with “exuberance,” a quality often absent in today’s baseball. “That’s what defined Mays as a player.” She’s right … and you should consider it a blessing if you’re old enough to have watched him play. It was immensely fun.

On Fox’s pregame show, Derek Jeter provided this perfect assessment: “Willie Mays played with a style, he played with a flair that no one had or no one had seen up to that point. He exuded joy on the field. He broke the norm … He made the game fun to watch. Look, we played professional baseball as a sport, but we’re still entertainers. We’re entertaining the fans. (Mays) was at the forefront of that.”

Even though it’s sad that we no longer have the Say Hey Kid, MLB at Rickwood reminded us that it’s OK to feel joy attending a baseball game.

+ + + +

Two final observations: the people of Birmingham are genuinely first-class. Their friendliness showed through at every opportunity. MLB, bring this event back here!

Second, I’ve been asked on numerous occasions for my thoughts on the timing of Willie Mays’ death. I know that until my last day on earth, I will remember exactly where I was when I heard the announcement on Rickwood’s PA system.

Second, I’ve been asked on numerous occasions for my thoughts on the timing of Willie Mays’ death. I know that until my last day on earth, I will remember exactly where I was when I heard the announcement on Rickwood’s PA system.

His passing came as the baseball world was converging on his hometown of Birmingham to honor the Negro Leagues in general and Mays in particular. My friend and columnist at USA TODAY Gabe Lacques called the timing “downright heartbreaking.” Mays lived to age 93, but the fact that he passed on the exact day that he did simply can’t be coincidence.

I don’t claim to comprehend the complete cosmic significance of this, but there’s no denying there’s enormous meaning in it. The fact that he went to heaven as MLB had gone to great efforts to have every living Negro League veteran come to Birmingham is profound. As his son Michael said to the crowd just before the first pitch on June 20, Willie was listening from up above, so yell really loudly for him. Even those of us in the rows of media seats couldn’t help but stand and cheer.

Willie, God blessed you with uncanny talents. He blessed all of us who got to watch you. There’s no debate that you made your home city proud. You made your race proud. You made all of baseball proud. And you made the country proud.

Rest In Peace.

It would be great if you made a contribution to the Friends of Rickwood, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation charged with preserving the ballpark and restoring it to its former glory.

Provide a comment below with your thoughts about the events at Rickwood Field or these articles.

Outstanding, outstanding work, Joe. You can take a topic that people don’t know much about and in a couple pages make them an expert with your reporting of history. It’s not only great to learn about the history of a classic ballpark, your writing and enthusiasm make me want to make a trip there! Very well done, Mr. Mock.

I really enjoyed reading this and the way you chose to structure it. It’s awesome to hear about all the folks who are so passionate about the field and were excited for the event – fans, players, senators!