Articles and photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

Much of this content originally appeared in USA TODAY Sports Weekly and on USATODAY.com. Used by permission.

BIRMINGHAM, Alabama The official nickname for Birmingham is “The Magic City.” It received this label because of the its stunning growth in population a century ago. It was said that it grew “like magic.”

| Ballpark Stats |

|

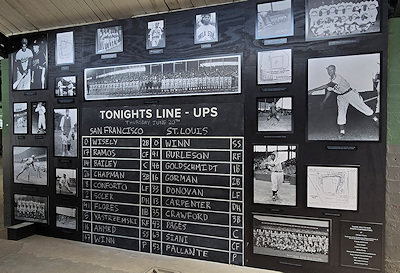

| Teams: St. Louis Cardinals playing as the Stars and the San Francisco Giants playing as the Sea Lions |

| MLB game: June 20, 2024, a 6-5 win by the Cards over the Giants |

| Attendance: 8,332, a sellout |

| Dimensions: LF – 324′; CF – 400′; RF – 332′ |

| Vendors that prepared the park for MLB: BrightView, Populous, BaAM |

| Cost of renovations: undisclosed, most of it funded by the City of Birmingham (estimate is $6 million) |

| Field points: South by southeast |

| Playing surface: the new sod is Tahoma 31 bermudagrass |

| Betcha didn’t know: The name of the ballpark came from a “name the park” contest in 1910. The winning entry combined the team owner’s first name with part of his last. |

On June 18, 19 and 20, 2024, the city indeed hosted a magical event. Major League Baseball came to town, bringing three days of games, concerts, charity events and most importantly, honors for the sport’s Negro Leagues.

This was accomplished so well that (as you will read below) president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Bob Kendrick told me “Any of us charged with being the stewards of the history of the Negro Leagues can’t help but feel a sense of pride about this.

“So proud. So proud.”

What follows is a series of articles about the event known as MLB at Rickwood. These cover: the incredibly rich history of the 114-year-old park; how MLB got it ready to host big-league baseball; what different fans and stakeholders had to say about this historic event; and my observations of the most noteworthy goings-on that week.

This is a very different format than our typical in-depth review when a new ballpark opens. But none of us were around when Rick Woodward built this ballpark (mostly using his father’s money) in 1910, so it deserves a different kind of format — and a very thorough treatment.

Let us know what you think of all of this in the comments section at the end of page two.

SUCH A RICH HISTORY — BUT SOME OF IT TAINTED BY SEGREGATION

NOTE: this appeared in USA TODAY Sports Weekly the day before the June 20, 2024 MLB game at Rickwood Field

In the 1950s, Birmingham, Alabama had a city ordinance called Negroes And Whites Not To Play Together. Section 597 made it against the law for “a negro and a white person to play together or in company of each other in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, baseball, softball, football, basket ball [yes, two words] or similar game.”

Historians often refer to this as “the checkers ordinance.”

A name synonymous with Southern segregation was Eugene “Bull” Connor. He was a powerful political figure in Birmingham at the time, and his zeal in enforcing Section 597 was legendary – and not in a positive way.

The issue came to a head in the fall of 1953 when an all-star baseball team organized by Jackie Robinson was scheduled to play a barnstorming game at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. Because the roster was integrated, Connor did everything he could to block the game. In turn, Robinson agreed to play only the Black players to avoid having both races on the field.

The following April, Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers (including Black catcher Roy Campanella) scheduled two exhibition games in Birmingham against Hank Aaron’s Milwaukee Braves. With a referendum regarding the checkers ordinance about to be contested in a city election, the games were permitted to proceed.

In those days, Black fans were allowed to attend “white” baseball games, but they were restricted to “colored only” sections in the right-field corner. For the two exhibitions, those seats were packed, with thousands more Black fans standing all around the outfield. The sections reserved for whites were practically empty.

This marked the first time both races were represented on the same playing surface at Rickwood Field.

This is just part of the rich history – some of it heartwarming and some infuriating – of the facility dubbed America’s Oldest Ballpark. When fans attend Major League Baseball’s regular season game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants here on June 20, there will be a new slogan about Rickwood on caps and t-shirts: History Played Here.

It’s an apt phrase for a stadium that opened 114 years ago. It’s also the rare facility that has gone by only one name for its entire life, as it was named for Rick Woodward. He was the son of iron magnate Joseph H. Woodward, who disapproved of his son’s fascination with the fast-growing sport of baseball.

Renting to both the Negro Leagues and the KKK

In 1909, the young Woodward acquired controlling interest in Birmingham’s Minor League team, the Barons – a team nickname still used by the city’s Southern League franchise. His first order of business was replacing the team’s all-wooden ballpark with a structure based on concrete and steel – the first such stadium in the Minors and only the fifth such baseball facility overall (Shibe Park, Forbes Field, Comiskey Park and League Park were the first four).

Enlisting the help of Connie Mack, who had overseen the design and construction of Shibe Park for his Philadelphia Athletics, Woodward pushed forward with the construction of Rickwood Field. Even then, cost over-runs were the order of the day, as the outlay to build the facility reached $75,000 when the budget had been $25,000.

Jubilation was the reaction of the city of Birmingham to its new ballpark. After witnessing the joy of the overflow crowd of about 10,000 at opening day on August 18, 1910, the elder Woodward decided to retire the debt created by his son’s expensive construction project.

With the Barons’ financial stability assured, Rick Woodward remained the team’s owner through 1938. Ever the shrewd businessman, he rented Rickwood to Negro League teams on weekends when the Barons were on the road, and would even rent the park to the Ku Klux Klan for cross-burning rallies.

Until the franchise went dormant in 1961 when it refused to integrate its roster, the Barons competed in the minor league known as the Southern Association. The winner of that circuit’s playoffs would then face the champions of the Texas League each year in what was called the Dixie Series.

The Barons captured the Dixie Series six times, but the most talked-about tilt was in 1931. That’s when 20-year-old fireballer Dizzy Dean led his Houston Buffs into Birmingham. The brash right-hander taunted the Barons by threatening to pitch with his left hand against them. “That way they’d have a chance.”

At the time, the throng that showed up at Rickwood was the largest to attend any sporting event in Alabama. The Barons’ 43-year-old Ray Caldwell outpitched the cocky Dean in a 1-0 Birmingham victory. The game was “the touchstone of Birmingham’s baseball experience, forever etched into the city’s collective memory,” wrote Timothy Whitt in “Bases Loaded with History,” the book that serves as the definitive account of Rickwood Field.

Whitt told USA TODAY Sports that he feels there’s something about Rickwood Field “that has a religious quality to it, that it is a holy place. For years, they didn’t play baseball on Sundays so fans could go to church. The rest of the week was for the Church of Rickwood.”

The Friends of Rickwood, created in 1991 to oversee the preservation of the park, keeps track of the number of Baseball Hall of Famers who have played at Rickwood. It’s a staggering number: 182. When you consider the opposing teams in the Minors, the barnstorming Major Leaguers (Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and many more), and all the Negro League stars, you can see how it could be this many.

“It is an incredible group of players who walked onto this field,” says Whitt. “I think it’s more than in any other stadium in baseball.”

Preserving the landmarks

But it’s not the history of the Barons or the barnstorming big leaguers that prompted MLB to bring a game to Rickwood. It’s the fact that the Negro Leagues fielded teams here from 1920 until the circuits disbanded in 1960. Some years the team was in the Negro American League, some years the Negro National League and others in the minor league Negro Southern League – but the team was always called the Black Barons.

And their home park was always Rickwood Field. Precious few ballparks that hosted Negro League teams are still around. “We should preserve these landmarks,” observes Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. “Oftentimes they face the wrecking ball, and, yeah, you can rebuild them, but you can’t rebuild that history.”

Kendrick was part of the planning committee to bring the MLB game to Rickwood. “What impressed me the most is that when they had that game in Dyersville (Iowa), there was tremendous sentiment from fans to do something similar to honor the Negro Leagues. And baseball listened.

“This is going to be one of those seminal moments in Black baseball history. I don’t think I’m overstating how tremendously impactful this is going to be.”

“This is going to be one of those seminal moments in Black baseball history. I don’t think I’m overstating how tremendously impactful this is going to be.”

You’ll hear Willie Mays’ name frequently during the proceedings surrounding the MLB game. He grew up in the Fairfield neighborhood less than two miles from Rickwood. In 1948 as a 16-year-old high school junior, the phenom joined the Black Barons. By the end of that season, he was the starting center fielder for a club that won the Negro American League pennant.

After another solid season with the Black Barons – while finishing high school no less – the New York Giants came calling, signing the Say Hey Kid to a contract in 1950. Mays went on to record one of the most remarkable careers in baseball history, culminating with a first-ballot trip to Cooperstown in 1979.

When Mays’ career ended, he was credited with 3,283 hits. Now, though, the official total is 3,293, as the Negro Leagues Statistical Review Committee has just completed three years of work incorporating results from the Negro Leagues into the big leagues’ record books. True, Mays had more than 10 hits with the Black Barons, but the box scores of many of his games couldn’t be found.

Mays was but one of many superlative players on the Black Barons. Some of Satchel Paige’s best years on the mound were in Birmingham, including 1929 when he set a Negro League record for strikeouts. Other Black Barons enshrined in Cooperstown are slugger Mule Suttles and hurler Bill Foster.

Because most years Birmingham played in one of the Negro “major leagues,” all manner of Black superstars played for opposing teams: Josh Gibson, who is thought to have the longest home run in Rickwood history; Oscar Charleston, who played or managed for 43 seasons; Cool Papa Bell, whose lightning speed was described in glowing terms in Birmingham’s newspaper; and a young Jackie Robinson who played for the legendary Kansas City Monarchs.

A field of real dreams

The Cards-Giants game on June 20 is meaningful on many levels, not the least of which is shining a spotlight on the undeniable importance of the Negro Leagues in baseball history.

Gerald Watkins is the chairman of the board for the Friends of Rickwood. He feels a big-league game in Birmingham is long overdue.

“Major League Baseball was very innovative in playing a game up there (in Iowa), but the Field of Dreams was a movie site,” he explains. “We have a real field of dreams here, because to use one example, Willie Mays was in the outfield here, looking up and thinking ‘Maybe one day I’ll be in the big leagues.’ So this is a field of real dreams.”

Says Whitt, “To be honest about it, I think Rickwood is a far better venue for a (Major League) game than the Iowa Field of Dreams. That was a field from a movie, and Shoeless Joe Jackson was a fictional character. The connection with Rickwood Field, though, is so incredibly real. You’re looking at a place where the real Jackson actually played in the Minors and as a barnstorming Major Leaguer.”

“Fans in the ballpark and watching on TV will see a Birmingham that they have not seen before,” adds Watkins. “It’s a place with a high quality of living and a community that came together to bring Major League Baseball here.” He feels it will also help raise the funds necessary to preserve the treasure that is Rickwood Field.

“I can’t think of anyone that’s ever come to Rickwood as a tourist or a ballplayer that’s left without a good feeling in their heart about baseball. That’s what we want.”

TAKING A “VERY GENTLE TOUCH” TO RENOVATING RICKWOOD

This also appeared in USA TODAY Sports Weekly the day before the MLB game at Rickwood

The year was 1992, the 82nd anniversary of the opening of Birmingham, Alabama’s Rickwood Field. But there was no birthday celebration.

It had been five years since the Birmingham Barons of the Southern League had moved out, preferring the safer neighborhood and modern amenities of a brand-new ballpark in the southern suburb of Hoover. With no tenant, local residents who’d grown up attending games – both of the Barons in the white Minor Leagues and the Black Barons in the Negro Leagues – had a legitimate fear that Rickwood would be demolished.

“Birmingham had a great old building that was our terminal station for rail and bus travelers. It was a beautiful piece of art, but it was torn down in 1976,” recalls Gerald Watkins, the chairman of the board of the Friends of Rickwood, the non-profit tasked with preserving the ballpark. “Some of us were old enough to remember the terminal going away, and we thought we didn’t want to see this old ballpark go away the same way.”

The facility had fallen into disrepair by 1992. When an advance crew from Hollywood came on a rainy night to check out the site for possible use in a movie, there was nowhere for them to meet in the grandstands. That’s because water was pouring through the leaky roof everywhere they tried to gather.

With the aging park falling apart, Watkins feels this was the darkest point in Rickwood’s history.

But the filmmakers decided the vintage look of the park was perfect for their bio-pic of Ty Cobb. After all, Cobb was playing for the Detroit Tigers when Rickwood was built in 1910.

“The city mobilized. Big companies in town mobilized. The Friends of Rickwood were formed, and enough money was raised to get the ballpark brought to a level where the film could be done,” says Watkins. The film Cobb, starring Tommy Lee Jones in the title role, opened in 1994.

Notes Watkins, “that movie was the first inning of the rebirth of Rickwood.”

He admits that since the work done for Cobb, “It’s been very hard to get any big money to do the repairs that were needed.” Now the impending arrival of Major League Baseball for a game is giving this historic park another lease on life.

The San Francisco Giants will face the St. Louis Cardinals in a regular-season game at Rickwood on June 20. Fox will handle the nationwide broadcast of the sold-out contest.

Maintaining the magic

Before MLB decided to bring a game to Rickwood, they sent their own advance team in the winter of 2022 to see if it would be feasible. After all, the structure and playing field had been around for 112 years.

Murray Cook of Brightview has been MLB’s main field consultant since 1993, when he prepared ball fields in Eastern Europe in preparation for a series of games by U.S. Minor Leaguers. The visit to Rickwood a year-and-a-half ago marked the first time he’d seen the wooden ballpark. “It brought back memories of some of the old stadiums I’d worked in over the years,” he recalls. “It is a really unique, cool place.”

Despite that, the playing surface “was basically a rec-level field. It was in really poor condition. It was some weeds, some grass, some Bermuda (grass), some more weeds. And the dugouts were like bunkers. When you were standing in one, you couldn’t see the left fielder because there was a big bump in the middle of the field.”

Perhaps the biggest anomalies were the foul lines. “They’d been putting chalk down the foul lines for, what, 100 years. This made the line literally a foot higher than the field on either side of it.”

So there was no way to coax the surface back to health – or to being level. “We knew we were facing a challenge of building a new field that meets Major League quality in an existing venue that wasn’t designed to hold a regulation field.”

So the first order of business was to excavate and remove the top two feet of the playing surface. “That was the only way we were going to get this thing to grade.”

A system of pipes was then installed that could drain away rain water at a rate of seven to 10 inches an hour. Above that a layer of gravel was applied, then a blend of sand and dirt for the roots of the grass to grow into. Then bermudagrass sod was meticulously rolled on top.

A system of pipes was then installed that could drain away rain water at a rate of seven to 10 inches an hour. Above that a layer of gravel was applied, then a blend of sand and dirt for the roots of the grass to grow into. Then bermudagrass sod was meticulously rolled on top.

Cook’s crew was also in charge of replacing the dugouts, the backstop, foul poles and the fencing around the field.

Brightview also encountered two true clashes of yesterday and today. First, they had to erect netting all the way down the foul territory, very much unlike the screens of decades ago, which provided far less protection to fans. Second, the existing light standards actually protrude from the top of the roof over the field (see photo). “Those lights are part of the charm and history there, and we didn’t want to take them down. So since (the lights) don’t meet code, we left the fixtures and took out the lenses and bulbs, so if a ball did hit them, you wouldn’t have glass crashing onto a player.”

The lighting for the MLB night game will come from temporary light standards, brought in on flatbed trucks.

“The big challenge with Rickwood was to ensure we maintained the magic and history of the venue,” says Cook.

Creating the pallet

In recent years, MLB has staged events in venues where none had existed previously. Examples include the pop-up ballpark built on an abandoned golf course at Fort Bragg, North Carolina in 2016 and the incredibly successful Field of Dreams games in the cornfield in Dyersville, Iowa the past two years.

“This project isn’t a ground-up build, where you’re building everything from scratch,” observes Todd Barnes, principal at architecture firm Populous. “In this, we were handed a stadium that is very old and doesn’t meet code in many ways. We had to fit Major League Baseball into a place that was never intended to have it.”

“Rickwood was never built in scale for any occupancy of this size,” adds Populous associate principal Michael Kinard. “We have to provide almost all the facilities that are required for the event, from clubhouses to the operational area to media functions.”

“Rickwood was never built in scale for any occupancy of this size,” adds Populous associate principal Michael Kinard. “We have to provide almost all the facilities that are required for the event, from clubhouses to the operational area to media functions.”

The park’s tiny locker rooms and pressbox didn’t come close to doing the job.

What little parking had been adjacent to Rickwood is now occupied by a complex of temporary structures housing all of the functions needed to host a modern-day MLB contest. This means fans will have to park at Legion Field a mile away and take shuttles to the ballpark.

“The goal was to take a very gentle touch to it,” says Barnes. “Obviously, we didn’t want to overhaul a historic building. (Rickwood) speaks for itself with a very historic legacy and look and feel.”

For example, to meet modern-day ADA requirements, no new structures were added. Instead, existing seats were removed to accommodate wheelchairs.

“We love these kinds of challenges and accept them with open arms. These are the best games for us overall,” explains Barnes. “We’re creating the pallet for MLB to frame the right game presentation to make it just an incredible day.”

Keep reading for more on this “incredible day.” Page 2 provides comments from various folks involved with the event, plus my ten observations of the impact of MLB coming to Birmingham. Click below! And please make sure to leave a comment at the end of the second page.