Article and all photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

Nashville has certainly provided its sports and music fans with outstanding facilities. Bridgestone Arena is one of the NHL’s showplace venues, and when the Country Music Association Awards Show is held there, it is a spectacle. Across the street, the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum is the nicest facility of its type in America, and, yes, that includes the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.

Ballpark Stats |

|---|

|

| Team: Nashville Sounds of the Pacific Coast League |

| First game: April 19, 2015, a 3-2 10-inning victory over Colorado Springs |

| Capacity: 10,000, including 7,500 fixed seats |

| Architects: Populous was design architect and Hastings was architect of record |

| Construction: joint venture of Barton Malow, Bell and Harmony |

| Price: $47 million for the ballpark itself |

| Home dugout: 3B side |

| Field points: south by southeast |

| Playing surface: Tifway 419 Bermudagrass |

| Betcha didn’t know: The southern perimeter of the park’s site is over a 21-foot-diameter sewer line that dates back 100 years. |

The numerous music venues, especially the Ryman Auditorium, are well known. And the NFL’s Tennessee Titans play in as nice a stadium as there is in pro football.

Yes, the city had its bases covered … except where bases were literally concerned.

Nashville’s baseball stadium didn’t measure up. In fact, it was downright awful. Easily, Greer Stadium was the worst of the 30 Triple-A ballparks in the land. In my opinion, it was a real embarrassment that in a city with such front-row facilities, baseball was relegated to the bleachers.

Over the past 15 years, there have been many proposals to rectify this with a brand-new ballpark. Thankfully, no one championed the cause of simply sprucing up the aging Greer. No, there was no rehabilitating its structure or surroundings.

Those proposals always faced three problems, and those three issues varied in their importance in each proposal: money from the local government; money/financing from the team; the location for a new park.

An extremely promising proposal was made in 2006. It focused on constructing several projects on the banks of the Cumberland River just a few blocks from the edge of downtown, on the long-abandoned site of Nashville’s Thermal Transfer Plant. The centerpiece was a $43-million ballpark designed by HOK (now called Populous). The underlying financial arrangements involved the team borrowing $23 million from a consortium of a dozen Tennessee banks, while the other $20 million would come from a combination of the developer, who would’ve constructed retail space and condos next to the ballpark, and from tax-increment financing. In addition to providing the land, the city committed $500,000 a year to help with the park’s operating costs.

The team, the Sounds of the Pacific Coast League, had been hoping to move into the 12,500-seat facility in 2007 or 2008, but there were so many delays that the project was pushed back to 2009 … and then to “never.” The Metro government authority (the City of Nashville and Davidson County) finally ran out of patience with the lack of progress by the team in arranging the financing, so when a solid deal failed to materialize by a deadline of April 15, 2007, the government pronounced the project dead. And the Sounds continued to play at the worst ballpark in the PCL.

| There and back again |

|---|

|

| The new ballpark sits on the same site as Nashville’s Sulphur Dell, home to pro baseball for eight decades. Then from 1978 through 2014, it was played at awful Greer Stadium (below). |

|

This was certainly a low point in the story. While the team didn’t threaten to move out of Nashville, it was only natural to consider the possibility that a market with the NHL and NFL wouldn’t have any pro baseball at all.

To be fair, the problem with the team holding up its end of the bargain occurred with the Sounds’ former ownership group, Amerisports Companies. In 2009, MFP Baseball (principally the investors Frank Ward and Masahiro Honzawa) acquired the franchise, and instantly there was renewed interest in a new ballpark. According to published reports, the new owners still wanted the park to be located at the Thermal Transfer Plant site, which indeed was a desirable spot.

The City, though, had a different site in mind, because they wanted the so-called “Thermal site” to become a municipal park with an amphitheater. Instead, the City focused on an area north of the business district, not far from the Tennessee State Capitol. And as fate would have it, it was a spot with unbelievable historical significance in the sport of baseball, because it was the location of one of the most famous Minor League ballparks ever, Sulphur Dell.

Apparently, the City persuaded MFP Baseball to consider the new location, and after viewing the neighborhood that surrounded the site, the owners warmed to the idea. The framework for a deal finally came together — although it was by no means a straightforward process.

The State of Tennessee, you see, owned several blocks of land between 3rd and 5th Avenues, bounded by Jackson Street to the north. This site was the most desirable for the ballpark, although the City already owned the plot of ground just to the south of this. Since the State wanted more parking capacity for State workers, and because the ballpark would also need parking, a “land swap” was worked out between the State and the Metro government. The State received the City’s parcel so it could construct a parking garage (that would also be used for baseball parking), and the City obtained the land to build its ballpark.

For those of you keeping score at home, the complicated financing looked like this (and many thanks to Bonna Johnson of the Mayor’s office for helping me piece this together):

- Although the ballpark was only a part of a $150 million development package for this neighborhood, $65 million was earmarked for the stadium ($37 million for construction, $23 million to the State for the land, and $5 million for “capitalized interest” during construction);

- The bonds issued for this created an annual payment debt for the Metro government of $4.3 million, which would be covered by $700,000 rent from the Sounds, redirecting sales-tax revenue of $650,000, property tax revenue from the various developments of $1.425 million, TIF (tax-increment financing) of $520,000 plus the elimination of two budget items worth $660,000. The remaining $345,000/year came from the Metro’s operating budget;

- As for the land, the Metro Council received from the State the parcel for the ballpark plus adjacent greenway land, plus another 28 acres elsewhere that Metro had been leasing from the State. In exchange, the State received from Metro $18 million to build the parking garage next to the ballpark and $5 million to build an underground parking garage whenever the State builds a Tennessee State Library and Archives. The deal also includes a swap of land between Metro and the developer Embrey.

- The Sounds agreed to a 30-year lease with rent being $700,000 a year, plus the team has to cover the cost of operating and maintaining the ballpark.

With the financing in place and the land “swapped,” it was a joyous day when ground was finally broken on the park on January 27th, 2014.

On March 3rd, the excavation for the sunken playing field began, and the following month, First Tennessee Bank announced it had acquired the naming rights, so the stadium would be called First Tennessee Park.

Best quip |

|---|

|

At the dedication ceremony moments before the gates were opened at First Tennessee Park, Michael Crowley, the president of the Oakland A’s (the brand-new parent club of the Sounds), commended all involved in the accomplishment. He added “We know how difficult it is getting a new park built.” |

All of this would’ve been perfect except for one thing: cost overruns.

With only a couple of months until the park’s opening, Metro calculated that the actual construction cost wasn’t going to coming in at the budgeted $37 million. Or even close. It was going to cost $47 million, thanks to a horrible winter that delayed construction (and would take lots of overtime to make up), the discovery of contaminated soil that required “environmental remediation” and the addition of several upgrades to the park requested by the Sounds. The most notable upgrade was a new guitar-shaped scoreboard, as Greer Stadium’s only positive attribute was its similarly shaped scoreboard.

This eight-figure funding gap was taken in stride by Nashville’s Mayor. “When you have a fast-moving project with a fixed deadline, more often than not you encounter these types of budget challenges as you move from concept to construction,” Mayor Karl Dean said in a press release. “The good news is that Metro Government has the funds to cover the additional expense in a way that does not impact other city programs and projects.” This gap was plugged by the following: $2 million that the Sounds agreed to pay (largely because the new scoreboard was their idea); the fact that the sale of bonds actually generated more revenue than originally forecasted; the increase in property taxes in the area of the new park; TIF revenue that had been held in reserve.

Problem solved.

Work continued at a fever pitch, and when I rolled up to the new park about nine hours before its inaugural game, construction workers and landscapers were still scrambling.

This flurry of activity all led up to the moment you see at the top of this page, when Nashville’s Arnold Leon hurled the first pitch at First Tennessee Park.

After decades of waiting for an upgrade for Greer Stadium, Music City finally had a baseball facility that was on a par with the Titans’ stadium and the Predators’ arena. But does First Tennessee Park measure up to other recent-vintage ballparks in Triple A? And what about that much-discussed location? Is it all it could be? Read on as we delve into the park’s site, exterior, interior and fantastic amenities.

The Setting

Consider how baseball in Pittsburgh came full circle, geographically speaking. At the turn of the last century, the Pirates (with all-time great Honus Wagner at shortstop) played at Exposition Park, on the north shore of the Allegheny River, directly across from downtown Pittsburgh’s “Triangle.”

The park suffered through many floods, and when owner Barney Dreyfuss decided to build a new palace for his team, he selected a spot that couldn’t have been more different. Miles away from downtown, on the top of a hill in the neighborhood of Oakland, he constructed the finest ballpark of the day, Forbes Field, which opened in 1909.

When the six-decade-old park had outlived its usefulness, Pittsburgh built a multi-purpose stadium in 1970. Where was it? Across the river from the downtown Triangle. And when Three Rivers Stadium needed to be demolished, the Pirates moved less than a mile away, into PNC Park, which is only a couple of hundred yards from the site of, you guessed it, Exposition Park. You can find the historical marker for the ballpark on the sidewalk that curls along the river’s churning edge, just down the steps from PNC Park’s Bill Mazeroski statue.

Not since the Pirates moved back to the river bank has a baseball team’s home completed such a full-circle … until now.

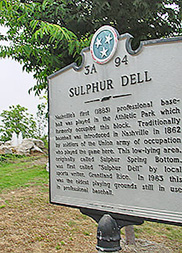

In the early 1860s, Civil War soldiers started playing the new sport of baseball on a plot of ground in Nashville between the State Capitol and the Cumberland River. Within a few years, organized teams began playing regularly scheduled games here, and the spot became known as Sulphur Springs Bottom because of the adjacent sulphur springs.

The springs often gave the area a distinctive odor, and a nearby dump added to the unpleasant smell. That didn’t stop grandstands from being built around the oddly shaped playing field, that was sunken 20 feet or so below the level of surrounding streets. This created sloping ground in the playing field.

Pro baseball was played here starting in 1885, and the facility was called Athletic Park. One of the most famous sportswriters of the 20th Century, Grantland Rice, hung the nickname of Sulphur Dell on the place, and the name stuck.

|

As the Yankees were terrorizing the American League in 1927, Sulphur Dell went through a radical change: the playing field was turned by 180 degrees. This was done “so the sun would not be in the batter’s eyes,” according to historian Skip Nipper. This meant that the grandstand moved from the northern corner of the parcel to the southern. Interestingly, that meant the grandstands were nestled up against the right-of-way of a buried sewer line (more on that in a minute). Nipper added that “from then until the 1950s, very few changes were made” to the park.

So during the last four decades of Sulphur Dell’s existence, the incline in the playing field started from the RF foul line across to left center. The right field foul pole was a mere 262 feet from home plate — but its adjacent fence was 22-1/2 feet above the level of most of the playing field. The incline wasn’t due to the presence of the buried sewer line, as you might have guessed. No, it was due to the proximity of 4th Avenue directly behind the RF wall. See the unusual arrangement in the photo above, which Wikipedia attests is in the public domain.

The final season for pro baseball here was 1963, and the place was eventually leveled in 1969. The sunken field was filled in with chunks of concrete as well as dirt, rocks and other debris. It eventually became a parking lot for State employees.

Why is all this important? Because First Tennessee Park (FTP) is located where Sulphur Dell hosted baseball for a century. In fact, much of the misshapen playing field of the old park was located where the new park’s RF is today. “This is arguably the most historic site in the country for a ballpark,” noted Steve Boyd, of Populous, the architectural firm that designed the park.

I love this historical tie-in, and the city and the team deserve a lot of credit for doing this. And they almost got the site selection of the new park exactly right … but they didn’t build the shiny new ballpark in the very best spot, however.

Building in this neighborhood makes sense for numerous reasons: the view of the skyline it allows; it provides a bridge between the bustling commercial success of the area to the south with a needy neighborhood to the north; there is great potential for commercial development and a new State Library close by.

However, the exact parcel that today holds the $47-million building is a block too far to the south. The cross street directly in front of the main entrance of the ballpark is Jackson Street, by no means a heavily used thoroughfare. One block to the north is Jefferson Street, a major through street that carries many cars across the Cumberland River just a few blocks from the park. An entryway as beautiful as the one at First Tennessee Park deserves to be seen by a lot of vehicular traffic. Instead, it’s almost invisible from Jefferson.

The space between the ballpark and Jefferson is made up of two blocks. One, bounded by Jackson, 3rd Avenue, Jefferson and 4th Avenue, is largely made up of abandoned houses, plus a couple of currently occupied commercial buildings and their parking lots. The other block contains the construction site of an ambitious condo or apartment complex. When it is completed, there’s no way you’ll be able to see FTP over these high-rise buildings.

I asked Boyd about this error in the exact placement of the park. “We realized this early on,” he explained. “We suggested that the ballpark be built one block farther north, but we were told that since the state didn’t own those two blocks, it couldn’t be done.”

|

Let’s examine the rest of the park’s surroundings. On the west side are parking lots largely used by state employees, although 5th Avenue (that separates the park from the lots) is a lovely tree-lined boulevard (above right). Interestingly, the parcel of land just to the north of these parking lots on the west side of 5th is targeted to become the Tennessee State Library and Archives one day. It will have underground parking beneath it, which will provide an additional parking option for fans attending games at FTP.

On the south edge of the park’s perimeter is a mass of construction, principally for the parking garage that won’t be completed for the inaugural season at the ballpark.

|

On the southeast corner are some attractive condos. Residents can sit on their balconies and watch the goings-on inside the park (above left). Separating the park and the condos, by the way, is a “greenway” that follows the winding path of a 100-year-old sewer pipe buried about 20 feet under the ground. Nashville’s building code has quite a few rules that must be followed when construction is going on above the massive 21-foot-wide, brick-lined flow line. That might have necessitated that the sunken playing field of FTP be built entirely north of that line. Of course, as we’ve discussed, it would’ve been better had the stadium been built a block farther north than that.

It’s also noteworthy that one of Nashville’s better steakhouses, The Stock-Yard, is a block to the east on 2nd Avenue.

Between the park’s footprint and 3rd Avenue is a strip of grass and gravel that is being left for future development (above right). I was told that it would most likely be more condos such as the ones just to the south of this parcel, or perhaps a hotel. On the other side of 3rd Avenue is a series of small private parking lots.

Yes, there are numerous opportunities for further commercial development in the areas within a couple of blocks of the park. That’s one reason this neighborhood was a good choice for this project … but the link with baseball history on this site is the real winning factor of the location.

As you venture a little farther out, you’ll find beautiful new condos on the north side of Jefferson, and to the south, there is Nashville’s venerable Municipal Auditorium, and two blocks from there, the State Capitol. Three blocks west of FTP is the Nashville Farmers Market.

The Exterior

While much of First Tennessee Park’s perimeter is a work in progress, the north-facing entryway to the park is both beautiful and stately — and at night (below left), it’s simply spectacular. Again, it’s a shame more motorists won’t get a good look at it.

|

When you look at the building materials in daylight (above right), you see two contrasting looks: a zinc-like material on the top that is reminiscent of another Populous project, Tulsa’s ONEOK Field. Below that, the designers selected a material called TAKTL, “which of all building materials comes the closest to looking like a guitar,” Boyd explained.

On the north face of the park, just to the left of the numerous entry gates behind home plate, are the ticket windows. These look like none I’ve ever seen before — and if anything, during the day, the reflective glass on the building’s exterior prevents you from being able to tell that there are humans behind the glass to sell you tickets (below left).

Unfortunately, the attractive look of the stadium’s front doesn’t extend all the way around the ballpark. Most of the exterior perimeter on the west and south sides is simply iron fencing (below right). This has the added benefit of allowing pedestrians to peer into the ballpark, in much the same way that people outside of Charlotte’s excellent BB&T BallPark can look inside through the fences.

|

There are two entryways on the western side of the property. One is about halfway down the perimeter (below left), and it has lovely landscaping around it — all of it planted just a couple of hours before the gates were used for the first time. The other is at the southwest corner. It has a ticket office, and will be where patrons parking in the under-construction garage will enter. Here, you are entering right below the backside of the famous guitar-shaped scoreboard (below right).

|

While the eastern edge of the park along 3rd Avenue was very unfinished when the facility opened (leaving mostly chain-link fencing along the edge of the property — see below), the iron fences on the west have a good, permanent look to them.

|

So if you think about FTP’s exterior overall, you would conclude that the “front” of the park, where the main entryway and ticket windows are located, is spectacular, but the other three sides aren’t all that impressive. This is a good place to start making a few comparisons. First, how does the exterior of Nashville’s new park compare with the outside looks of the two most recently opened Triple-A parks? Those two parks are in Charlotte and El Paso, and both have spectacular exteriors. El Paso, with its stunning, soaring stained glass mural depicting the area’s rich history, has perhaps the most gorgeous look in the Minors. Sorry, but FTP doesn’t have any landmark elements to place its exterior in the class of elite ballparks. Again, the north-facing part of it is beautiful, but I’m not sure you’d say there is an “iconic” element to it.

The folks from Populous, however, feel that there were some very good reasons why this exterior differs so much from other recent parks. FTP is “a modern expression of baseball. While some may prefer retro ballparks, the design here had to be contemporary to reflect the progressive architecture and culture of Nashville,” Boyd pointed out. “A retro ballpark simply wouldn’t have been appropriate to the design language of the city. We were most interested in capturing the modern, energetic, musical components that make Nashville unique. We did this through materiality and more abstract expressions of motion and color. First Tennessee Park is different than El Paso’s park — particularly because of budget and site — but Nashville as a city and the culture and history of baseball there are drastically different and our design respects that.”

Read on as we assess FTP’s interior.