Article and photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

DYERSVILLE, Iowa The first time Major League Baseball tried its hand at creating a “pop-up ballpark” for a big-league game, it was at the enormous military base in Fort Bragg, North Carolina in 2016. MLB spent about $5 million dollars on a state-of-the-art playing field and temporary structures for clubhouses, stands, concessions, media … and, oh yeah, lots of port-a-potties.

| Ballpark Stats |

|

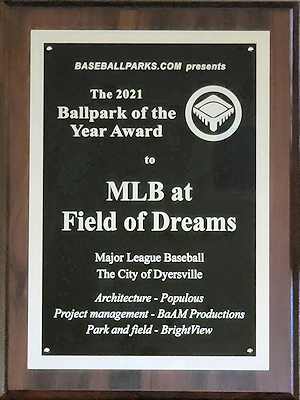

| Award: 2021 BaseballParks.com Ballpark of the Year (press release) |

| Used for: Regular season MLB game |

| First game: August 12, 2021, a 9-8 walk-off victory for the White Sox over the Yankees |

| Capacity: 8,000 |

| Dimensions: LF – 335; LCF – 380; CF – 400; RCF – 380; RF – 335 |

| Architect: Populous — Todd Barnes, Senior Principal |

| Construction: coordinated by BaAM Productions |

| Field and ballpark consultant: BrightView |

| Price: $6 million |

| Home dugout: the White Sox used the 3B dugout |

| Field points: northeast |

| Playing surface: Blend of three bluegrass seeds |

| Betcha didn’t know: Even though the flattest portion of the cornfield was selected to build the ballpark, 30,000 cubic yards of dirt still had to be moved to make the playing field level. |

The facility was routinely referred to as Fort Bragg Field. After the game was played on the evening before Independence Day, the structures were hauled away, but the field was left for the Army to incorporate into a recreation center. Indeed, when I returned to Fort Bragg a year later to present our Baseballparks.com Ballpark of the Year plaque to the Garrison Commander, they took me by the site that held the ballpark. Aside from the nice green playing surface, you had no clue that a Major League stadium had ever existed there.

But that one-game-only facility had a name. And that name was engraved on the plaque presented to Colonel Brett Funck.

So as I was preparing a preview article for USA TODAY on a similar pop-up ballpark in a cornfield in Dyersville, Iowa, I was wondering what to call it. So I contacted someone I knew in the Communications Department at MLB Headquarters and asked him for the ballpark’s name, or at least how they are referring to it in official communications.

He told me that they’d never devised a name for the facility. Nothing like Dyersville Diamond or Ray Kinsella Stadium? Moonlight Graham Field? Nope. MLB simply refers to it by the name of the event being played there: MLB at Field of Dreams. Or sometimes “MLB Ballpark,” as it’s referred to on the wayfinding signs around the entrance to the movie site. Surprisingly, MLB hadn’t created a Twitter handle for the facility or game.

So we’ll go with MLB at Field of Dreams.

By the way, the Fort Bragg Game (Presented by Chevrolet, if you want to know its entire title) was a smashing success. It showed the concept of a pop-up park could truly host two big-league teams. There were huge ratings on ESPN Sunday Night Baseball, and it spawned numerous one-off (but very, very special) regular season games in unusual places: at the Little League World Series; at the College World Series; London … and now next to the site where Field of Dreams was filmed.

It isn’t precisely where the filming took place, but you do have to walk through that site to get to the new facility, and the way you do it is indeed quite special. More on that in a moment.

The game played August 12, 2021 isn’t special simply because it happened near a spot where baseball fans have made pilgrimages for three decades. It’s also the first Major League Baseball game ever played in the state of Iowa.

There were numerous special touches related to Iowa in this game. For instance, the umpires in the game wore patches that said “EC,” honoring ump Eric Cooper, who passed away October 20, 2019 at the far-too-young age of 52. He was born in Des Moines, Iowa, graduated from Iowa State and umped in the Midwest League on his way up the ladder to the Majors. He was an Iowan through and through.

| Annie got the crazy idea that she could talk me into buying a farm. — Ray Kinsella |

MLB also shuffled which umps were working this game so that Iowa native Pat Hoberg could call the balls and strikes that evening.

And then there’s the corn. Lots and lots and lots of corn. And this year has been a good year for growing corn, so the stalks are 10-to-12 feet tall, towering over the fans as they make their way to the ballpark … the park that really doesn’t have a special name.

If you’re reading this, you’re most likely a baseball fan. And almost undoubtedly you’ve seen Field of Dreams. Perhaps numerous times. Or as one friend of mine admits, he’s watched it 30 times. You can make a truly strong case that it is the best baseball film ever made. For me, it is my favorite movie of all time. I won’t go into what my emotional reaction is every single time I watch it, particularly the ending.

I had a chance to speak one-on-one with Dwier Brown, the actor who played Ray Kinsella’s father John in the movie (see photo). He’d come to Dyersville (for at least the two dozenth time, he told me) to see the miraculous pop-up ballpark. I admitted to him that in watching the movie many, many times, it’s almost worse when you know what is about to happen in a scene, because you start crying anyway.

I had a chance to speak one-on-one with Dwier Brown, the actor who played Ray Kinsella’s father John in the movie (see photo). He’d come to Dyersville (for at least the two dozenth time, he told me) to see the miraculous pop-up ballpark. I admitted to him that in watching the movie many, many times, it’s almost worse when you know what is about to happen in a scene, because you start crying anyway.

“It always gets me,” Brown told me. “People are always coming up to me to talk about their father and how the film affected their relationship. My dad died 36 days before I came here to shoot my scenes, so the father-son dynamic was unmistakable for me. And it really gets to me every time I come here.”

Field of Dreams isn’t just another movie. It moves people in a way few films do — and it moves people who aren’t typically moved by movies. As Commissioner Rob Manfred said, “Baseball brings people together and creates a common bond. Field of Dreams has done exactly that in the 32 years since its release. With characters and dialogue that are etched in our memories, the movie remains meaningful to this day.”

MLB wanted to play this game in 2020. When it was announced in August of 2019 (pre-pandemic, remember), the buzz was deafening. Everyone was talking about it. Phones at hotels in eastern Iowa rang off the hook. MLB was going to have a runaway hit on its hands.

You know about the 2020 season. As far as fans attending games, the regular season had a total attendance of zero. Games were shut down until July. The contest was kept on the schedule, though, even as the regular season started in July without fans. I was prepared to be there to cover it, as even though the facility was constructed without seats, I’d be in the pressbox. The inevitable happened, though, and the game was canceled. Not helping matters was the fact that the Cardinals were supposed to play the White Sox, and COVID kept knocking players from the Cards’ active roster.

So the structures were dismantled and put into storage. Very importantly, though, BrightView continued to maintain the playing field. Murray Cook, President of the Sports Turf Division of BrightView, told me that “we put the field to bed for the winter and woke it back up in the spring.” It’s a little more complicated than that, as Major League-caliber playing surfaces require enormous TLC. But the bottom line is that the team responsible for the playing facilities hit the ground running at the beginning of the 2021 growing season. This was being done with the intent of trying again in 2021.

| If you build it, he will come. — Body-less voice in the cornfield |

After three straight days with heavy storms and high winds – damaging some of the live corn stalks close to the ballpark – Thursday morning, August 12 arrived with the nicest weather of the week.

Everything about the event was a huge success, including a wild home-run barrage, with the Yankees and White Sox combining for eight long balls. We learned that either the ball really carries in the middle of a cornfield, or that a baseball has the same attraction for ears of corn as steel does with magnets.

Three of the homers happened in the pivotal 9th inning. Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton provided a pair of two-run homers to push the Yankees to an 8-7 lead, only to have Tim Anderson – who admitted to the media prior to the game that he’d never seen the movie Field of Dreams – win it with a two-run walk-off blast in the bottom of the 9th (see the photo at the top of this page).

Even in losing, Yankee Manager Aaron Boone couldn’t say enough about the experience. “That’s probably the greatest setting for a baseball game I’ve ever been a part of,” he told the media. “Major League Baseball has done an amazing job creating that experience. It was a pretty special game that unfortunately didn’t go our way, but as far as the atmosphere, the playing field, the perfect weather tonight, it was something to behold.”

| Unbelievable. — Terence Mann It’s more than that. It’s perfect. — Ray |

That’s really saying something considering when Boone was a Yankees player, he was a part of huge playoff battles with Boston, and during his stint as a broadcaster for ESPN, he worked the MLB games at Fort Bragg and the Little League World Series. As the Yanks’ manager, they played the Red Sox in London. So to say that this is the best setting he has experienced speaks volumes.

It’s a little unusual to apply our normal ballpark-review format for a game in a temporary facility, but we’re giving it a try. Read on for our thoughts on this incredibly impressive stadium … and along the way, we’ll throw in some dialogue from (and about) the movie.

The Setting

Manfred told the media prior to the game that he’d come to Dyersville to assess the feasibility of bringing a regular-season game to the Field of Dreams six years earlier. He spoke to the owner of the land and to local governmental officials. He then dispatched a team of experts – including Cook, Senior Principal Todd Barnes of Populous and President Annemarie Roe of BaAM Productions – to Dyersville to report on what it would take to make a game happen there.

| If you design and build it |

|

| Two very important people behind the design and building of the new ballpark are Todd Barnes, Senior Principal at Populous, and the President at BaAM Productions Annemarie Roe. |

Dyersville, of course, is a tiny town. Its population of 4,500 means there are 91 other municipalities in Iowa with more residents. Most importantly, it’s where the producers wanting to make the movie found the patch of farmland and perfect farmhouse to be the film’s setting. The town is 25 miles west of Dubuque, which is situated on the Mississippi River on the eastern edge of Iowa. In fact, part of downtown Dubuque was where the city scenes depicting Boston were shot.

Barnes told us that when the group arrived on their covert mission at the Lansing family’s farm just outside of town, it was overwhelming emotionally. “Just being able to see the original ballfield there, the wooden bleachers that Kevin Costner sat on, and the farmhouse, you just feel like you’re on the movie set. It hadn’t changed at all.”

His first thought was to turn Ray Kinsella’s ballfield next to the farmhouse into some kind of big-league stadium. Romantically, that would’ve been both wonderful and magical … but then reality set in. It simply wouldn’t be feasible for a lot of reasons:

- The ballfield wasn’t level, as deep right field was three feet higher than the infield. That was no big deal in the movie, but Major League players must play on perfectly level surfaces, and “it just didn’t seem right to change the conditions there;”

- Everything about the field – the quaint backstop, the adorable little bleachers that Ray is shown building in the movie, the lights – would have to be ripped out and replaced with regulation big-league structures;

- The construction would’ve shut down the commercial operations of the farmhouse (which is rented out for corporate events), little souvenir shops and Baseballism store –plus make the movie site off-limits to tourists – for months. That seemed unfair to Barnes.

| Hey, is this heaven? — ghost of Shoeless Joe Jackson No. It’s Iowa. — Ray |

All of these factors were rolling around inside Barnes’ mind as the group was invited to tour the farmhouse. As he went upstairs, he noticed the windowsill where Ray looked out at the ballfield one night in the film. As he looked around at the miles of cornfields, a thought popped in his head. Why not leave the movie site undisturbed, and carve out a patch of those fields for a pop-up stadium? In fact, from his vantage point upstairs in the farmhouse, there looked to be a level portion of the cornfields a couple of hundred yards to the west of the movie ballfield.

|

| This is where the Lansing family lived prior to the filming of Field of Dreams in 1988. It looks just the same as in the movie. The other photo shows the living room window where Ray Kinsella looked wistfully out at the snow-covered ballfield as his family celebrated Christmas. |

The group then sloshed through the muddy fields to that spot, and determined that this was going to be the home for a Major League game.

As Cook likes to put it, “We took home plate from the movie field and moved it 1,000 feet to the west.”

If you stop to think about it, staging a professional game in the middle of a cornfield requires, well, everything. There needs to be a perfect playing surface (Cook and his crew made sure of that). There needs to be structures for the players, umps, caterers, lights, concessions, etc., etc. But there also needs to be high-speed Internet, really strong cell service, phone lines, lots more irrigation than usual for the cornstalks adjacent to the playing field, and loads of electricity. All of those things were pulled together. Miraculous, when you think about it.

| Don’t we need a catcher? — Ray Not if you get it near the plate we don’t. — Shoeless Joe |

If you’ve visited the movie site, you’ll recall that the driveway between the farmhouse and Lansing Road is about 700 feet long. MLB decided to “rent” those fields on either side of the driveway – as well as ones directly across the road – to act as parking lots for the employees working on the project and fans that would attend the game.

Since nearly all fans heading to the game would be driving to the site on US Highway 20 that crosses Iowa going east-west, it was fortuitous that the farm could actually be accessed off of two different turn-offs from the highway. One is on some very winding country roads that intersect 20 near mile marker 296, and the other is the more conventional route that tourists have been taking to the movie site for decades. It exits 20 at a cloverleaf at mile marker 294, and takes you directly through the town of Dyersville.

Had there been only one way in and out, that would’ve made traffic on these two-lane roads quite a mess, particularly following the game.

The central business district of Dyersville couldn’t be more of a slice of Americana. Little shops, bars and cafes dot 1st Avenue (see photo above), and there’s even a building with an exhibit called If You Build It that shows how the film was made. I thoroughly enjoyed the time I spent at a coffee shop called Brew & Brew. If you come to visit the movie site, take some time to spend a few bucks in the center of town.

What did the big-league players think of coming to this spot in Middle America? Well, the two teams flew into the airport in Dubuque the morning of the game (which is highly unusual, as they usually arrive the night before), and boarded buses that took them through the tiny town of Farley and through the heart of Dyersville.

| Getting thrown out of baseball, it was like having part of me amputated. — Shoeless Joe |

Aaron Judge talked about that bus ride upon the team’s arrival at the complex. “It was pretty cool. Usually guys are on their phones or listening to music, but on this (bus) trip, everyone was glued to the windows looking at the scenery.” He added that bus trips between airports and hotels or ballparks are always through large cities, so this was quite a departure. And the players from other countries had never seen anything like the rolling farmland of Iowa.

The Exterior

Let’s look at the park’s exterior from three points of view: what separates the complex from the outside world; what the seating structures look like from the rear; the corn.

MLB erected barriers between the fields used for parking and the movie site (see photo above). The long, straight structures reminded me of a border fence, because it was all placed there to keep people out who weren’t supposed to be inside.

| I have just created something totally illogical. — Ray That’s what I like about it. — Annie |

Some of the barrier is made up of storage containers like are used on large boats transporting goods across oceans. Into the sides of several of these were carved ticket and will-call windows. The rest of the barrier is chain-link fencing covered with mesh. There were basically three entry points – one set of gates (with winding lines on the parking-lot side, like at an airport or amusement park) for fans, one set for media and staff, and in between were large gates so trucks and buses could get into the complex using the driveway that pre-existed all of this construction.

Not a pretty look, but necessary – plus this wasn’t erected to be permanent. It was originally scheduled to be dismantled as soon the 2021 game took place there.

Not a pretty look, but necessary – plus this wasn’t erected to be permanent. It was originally scheduled to be dismantled as soon the 2021 game took place there.

Next, let’s examine what the backs for the seating sections look like. After all, there was no need for expensive masonry. This is a pop-up park, meaning it needed to be easy to erect and easy to tear down.

If you look underneath the seating sections, you see an intricate network of metal supports. The concept of an erector set is what comes to mind. Yet there was a great deal of intentionality with the way these supports were arranged, allowing steps to be constructed so that fans approach their section from underneath the stands, like most college football stadiums. A closer look under the stands shows speakers imbedded in the supports, and a maze of walkways on ground level.

Except for where the stairs are carrying fans up and up to their section, these massive structures are covered by some kind of mesh to give it more of a finished look, even though everything is temporary. Even the scaffolding holding up banks of speakers were covered by this mesh (see photo).

I went back and looked at photos from the Fort Bragg Game, and all of the mesh there was black, as the official logo for that game had a black background. At Dyersville, the mesh was green, which is a better match for the corn.

| Field of Dreams is so fragile and so perfect, it’s like a miracle. A completely original and visionary movie about the love of baseball. This movie is about the soul of baseball. This is about the intangible, mystical, unspeakable things that people feel when they go to a baseball park. If you love baseball, I think it’s a real, real special movie. I think it’s one of the best movies I’ve seen all year. — Film critic Roger Ebert in 1989 |

And speaking of the corn, it is definitely part of the exterior of the ballpark. Early in the process, MLB recruited the two brothers who were already working the fields adjacent to the movie site. Cook refers to these young men as the “cornkeepers” for the project, and their story is fascinating.

Adam Rahe (pronounced “ray”), 41, and his brother Andy, 36, grew up on a farm not far from the Lansing’s land. In 1988, obviously everyone in Dyersville knew that a major motion picture – starring Kevin Costner, no less – was being filmed in their midst. “I remember when we were younger, we had a hayfield that overlooks where the filming was being done,” recalls Andy of the summer of 1988. “We’d sit up there and watch, especially at night. It was a big deal for all of us in the area.”

| Brothers in farms |

|

| The two “cornkeepers” on this project were Andy Rahe (left) and his brother Adam. photo provided by Adam Rahe |

After the movie became a national hit, tourists started flocking to Dyersville to visit the famous ballfield. “If you saw an out-of-state plate, you knew what they were looking for,” Andy adds. “We’d have to give them directions.”

“One thing we learned the hard way from Fort Bragg is that we need to get the field in the year before,” explained Barnes. Since the game was initially set for August 2020, that meant that the brothers needed to harvest the corn on about five acres of their fields earlier than usual in 2019. That allowed construction on the playing field to begin, and sod to be laid.

Aren’t the brothers out a lot money by not being able to farm those five acres? “Oh, Major League Baseball has been awesome to work with. They made sure that we were always taken care of,” explains Andy.

Adam Rahe understands the importance of the movie. “I think when you’re younger, you don’t think a whole lot about family. As we all age, it brings up a lot of memories of family and the time you spend with them. It’s pretty cool to be that close to a movie that has been so nationally recognized for baseball and, I think, for second chances with family or friends.”

They took the year delay in stride. “We look at last year as a dress rehearsal,” says Adam.

With actively growing stalks of corn touching the outfield fences and an entire patch growing adjacent to the foul territory down the 1B line (see photo), a lot of care went into tending for this very special crop.

With actively growing stalks of corn touching the outfield fences and an entire patch growing adjacent to the foul territory down the 1B line (see photo), a lot of care went into tending for this very special crop.

And since you’re dying to know, the entire fields of corn for as far as the eye can see is grown from seeds from DeKalb, a company that dates back to 1912 and since 2017 has been owned by Bayer. Several of the Yankees players were shown on TV playing with ears of the corn – Giancarlo Stanton carried an ear in his back pocket as he headed from the cornfields to the clubhouse – and several tried to eat it. Well, they probably figured out quickly that chomping into the kernels was a bad idea, since it wasn’t cooked, and all of this crop is known as “feed corn,” which is made into feed for livestock and used in making ethanol and other products. Humans eat “sweet corn.”

But it made for a good TV shot.

| Go the distance. — Body-less voice |

As the pre-game ceremonies were about to start and the 8,000 fans were settling into their seats, I ran into Adam behind home plate. He was there with his family and his parents, preparing to watch the game that he and Andy had helped to make happen. The smiles on all of their faces were unmistakable. Not only had one of the most beloved movies of all time been filmed in their backyard 33 years ago, Major League Baseball had brought the National Pastime to this cornfield.

Talk about dreams coming true!

Go the distance by continuing on to page 2 for a description of the ballpark and what it was like to attend a game there.