Article and all photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

|

In 2004, the Phillies opened a brand-new spring-training facility in Clearwater, Florida. As soon as they were done playing exhibition games that spring, they moved into brand-new Citizens Bank Park in Philadelphia.

| Ballpark Stats |

|

| Team: The Miami (formerly Florida) Marlins |

| First regular-season game: April 4, 2012, a 4-1 win by the Cardinals over the Marlins. |

| Capacity: 37,442 |

| Architect: Populous |

| Construction: joint venture of Hunt and Moss |

| Price: The ballpark itself cost $515 million. Another $94 million was spent on parking garages and the park’s surroundings |

| Home dugout: 3B side |

| Field points: Southeast |

| Playing surface: Celebration Bermuda grass |

| Betcha didn’t know: All of the seats in the stadium are dark blue, except the very first seat that was installed, which is red |

The Montreal Expos certainly had a tumultuous couple of years. They shuttled their home games between Montreal and San Juan in 2003 and 2004, not knowing if the franchise would be contracted or moved permanently, before ending up in Washington, DC in 2005.

But in the history of the sport, I’m not sure a Major League franchise has ever gone through a greater metamorphosis than the Marlins of 2012.

Think about it. The team has a flamboyant, controversial new manager in Ozzie Guillén. They’ve brought in high-priced talent like Mark Buehrle, Heath Bell and especially Jose Reyes. They’ve adopted new logos, uniforms and colors. Two players went through name changes, with Leo Núñez becoming Juan Carlos Oviedo and Mike Stanton trading “Mike” for “Giancarlo.” Showtime has cameras everywhere chronicling everything. Even the geographic designation changed, from “Florida” to “Miami.”

Oh, and they moved into a new ballpark.

So even without the opening of Marlins Park, 2012 was going to be a season of huge adjustments. Probably the biggest adjustment of all, though, is going from playing in the worst baseball facility in the Majors, the football facility last known as Sun Life Stadium, to getting used to air conditioning and the lack of rain at Marlins Park.

I won’t insult your intelligence and pose the rhetorical question “Was the move from Sun Life Stadium to Marlins Park an upgrade for the franchise?” Puh-lease! Moving from the worst outhouse to the best penthouse is about what we have here.

Despite the obvious advantages to such a move, it didn’t happen overnight. I’ve been writing for years about the Marlins’ struggles in trying to obtain a new ballpark. If for no other reason, the attendance was horrible in Sun Life Stadium, and in this situation, you’d have to give the stadium a lot of the blame. For instance, over the 2010-2011 seasons, the Marlins drew the fewest fans in the National League — and the Pirates, the next closest NL team, beat the Marlins by over half a million fans during that time. In fact, from 2005 through 2011, the team finished in the bottom three in attendance among all 30 MLB teams every year. Ouch.

| Couldn’t leave it soon enough |

|

| Joe Robbie Stadium. Pro Player Park. Pro Player Stadium. Dolphins Stadium. Dolphin Stadium. LandShark Stadium. Finally Sun Life Stadium. The oft-renamed facility worked great for football, but not at all for baseball. The upper-deck seats were awful for baseball, plus there was no overhang whatsoever to protect fans from sun and rain. The Marlins worked from their inception in 1993 to obtain a baseball-only facility. 2011 was the final season they had to endure playing in a facility that was not at all conducive to their sport. |

The franchise appeared quite willing to move to another market to escape Sun Life Stadium, but no other city would make them an offer they couldn’t refuse.

So the Marlins kept going to the Florida legislature looking for a handout. After all, they reasoned, the state had helped many cities build a ballpark to attract or keep spring-training, so why wouldn’t they invest in keeping an MLB franchise in the state for its regular season?

After coming up empty handed in Tallahassee, the Marlins, Dade County and the City of Miami finally came to grips with the inevitable: it was going to take a public-private partnership between those governmental entities and the Marlins to make something happen. When the University of Miami announced they were moving their football games out of the decrepit Orange Bowl — creating the desperate need to demolish the aging structure — the City and County realized that this would provide a site for a new baseball stadium. While the Marlins continued to lobby for a site in downtown Miami, the framework of a deal came together in December of 2007. The two governments would provide the land and pay their share of construction costs from tourist taxes, selling bonds and reserves, while the team would be required to provide its $155 million share up front, instead of over time. The team had to agree to spend 35 years in the new facility, plus it would also have to change its name from the Florida Marlins to the Miami Marlins. And needless to say, the new facility would be at the Orange Bowl site. It was projected to open in 2010.

The two keys to this deal were: no money from an often-reluctant state legislature would be required; voter approval would not be needed. A series of lawsuits were filed challenging whether voters had to approve this outlay of public funds, with former Philadelphia Eagles owner Norman Braman spearheading the call for an election, making seven different arguments as to why this was so. While these seven arguments worked their way through the courts, progress on the design and construction of the facility slowed, and the opening date had to be pushed back.

In November of 2008, a judge ruled on the seventh and final argument from Mr. Braman, finding in favor of the Marlins on all seven counts. Work began anew, and an opening date of 2012 was agreed upon. At no time, though, did the Marlins and their owner, Jeffrey Loria, yearn for an old-style, retro park.

No brick. No green seats. No hints of Ebbets Field.

According to Greg Sherlock, Principal and Project Designer of the architecture firm Populous, it wasn’t just that his design team was instructed not to go retro. “More importantly, Mr. Loria wanted a piece of art. This vision (for the ballpark’s design) liberated the architecture free from anything reminiscent of the past.” Thankfully, that also means there’s no hint of Sun Life Stadium in Marlins Park.

The Setting

If you turn the clock back to 2006, I doubt anyone with the local government or the Marlins stood up at a meeting and declared, “If only we could get our hands on the land that the Orange Bowl sits on, then we would have the perfect spot for our new ballpark!”

No, I’m sure that was hardly the case. And when it turned out the University of Miami was eager to have its players and students travel even farther in order to play home games at the Dolphins’ stadium, well, that really told you a lot about the Orange Bowl’s neighborhood.

But once it was clear that there was no use for the aging football stadium in the heart of the neighborhood known as Little Havana, City officials knew it had to be torn down. I’m sure those same City officials had to work really hard to convince the Marlins that they should be happy for their new ballpark to be located at the Orange Bowl site, since the team had been hoping for a spot in fashionable downtown Miami. A couple of downtown locations were discussed, but each was either too small or was needed for other governmental purposes.

|

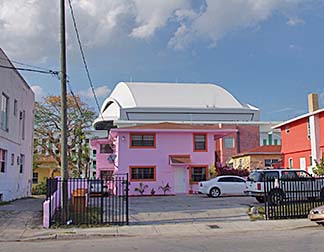

| Here are two views from 17th Avenue in Little Havana, five years apart. The one on the right shows the top of the gleaming new stadium rising above the surrounding neighborhood. |

So it came down to a “take it or leave it” proposition. This was quite reminiscent of what the Twins went through with the City of Minneapolis and the State of Minnesota, when they had to agree to abandon their longtime dream of having a retractable roof over their new stadium in order to get the deal done. Indeed, I’m not sure Target Field would exist today if the Twins had stuck to their guns and continued to insist on a $100-million moveable cover. In South Florida, I don’t think the Marlins would be playing in a new ballpark today if they would’ve continued their insistence that it be built downtown.

In reality, the areas of downtown that were being considered are a short two miles away from the Orange Bowl site. But, oh, those two miles take you from one world into a completely different one.

By no means am I trying to demean the fine people, many of Cuban descent, who live in Little Havana. I’m just pointing out the obvious: this location is not in an upscale, suburban neighborhood. Far from it.

And to be fair, most of Little Havana isn’t made up of gutted, grafitti-strewn buildings. The photos below show you two other scenes that are within three blocks of the new stadium — each showing the top of Marlins Park in the distance. But I will say this to you with no exaggeration: my hotel (Spring Hill Suites) was on the edge of Little Havana, and directly across the street from the hotel’s main entrance was a small house with two sheds in its fenced backyard, and chickens were running around the yard.

|

If you find yourself effectively locked out of all of the four large parking garages that anchor each corner of the stadium because you failed to purchase a parking pass online in advance, you might become frustrated. You might then set out in the residential areas around the park looking for a space on a street. You’ll notice that the vast majority of these streets sport signs that tell you that you can’t park on them when an event is happening at the stadium. I eventually found a street that did not have those signs, and parked. This was something that I never, ever would’ve done if it had been a night game I was attending, because I wouldn’t have wanted to walk back to my car late in the evening.

The following day, when it was indeed a night game I would be attending, I sweet-talked the shuttle driver at my hotel to give me a ride to the park, and I left my rental car at the hotel.

The bottom line of all this is that you have to be resourceful, and do your homework. Although it’s not the least bit obvious when you drive into the area of the stadium, there are several public lots about five blocks from the park, underneath the elevated Dolphin Expressway, at its interchange with 12th Avenue. It’s a fairly reasonable walk to the ballpark from those lots. Better yet, you can go online ahead of time and buy a parking pass for one of the parking garages adjacent to the stadium (and you’ll pay $15, instead of the $25 they’ll charge you on the day of the game if they have room).

But I maintain that there simply isn’t enough parking adjacent to this new facility. Sherlock disagrees. He feels there “is adequate parking in the vicinity, and patterns and usage will be optimized” as fans get more familiar with the area. He also points out that “Miami’s mass transit system is extensive and (it’s) evolving,” and as it does, access to the stadium will be enhanced.

Indeed, you can take the city’s old-and-reliable Metrorail to see the Marlins, but not directly to the ballpark. The closest the system of elevated tracks gets you to Marlins Park are the Culmer station and the Civic Center stop, both of which are just over a mile walk from the stadium. Miami Dade Transit helps to bridge the gap by providing the “Marlins Shuttle” from the Culmer station to the ballpark.

So where exactly is Little Havana in the Miami metro area? Well, it is situated almost precisely in between the city’s downtown and its main airport. The east-west highway that connects Miami International and downtown — and runs about half a mile north of the ballpark — is Dolphin Expressway. You would exit it at either 17th Avenue or 12th Avenue to see the Marlins play. Note that this expressway is a toll road.

|

But it’s the proximity to downtown that represents perhaps the only benefit of this location. It permits fans to see the city’s expansive skyline from within the ballpark (above). It is indeed an impressive sight — and the architecture takes full advantage of it, as we will see.

The Exterior

The exterior of Marlins Park is nothing short of stunning. Is it a fit in the surrounding neighborhood? No way. Camden Yards’ look is similar to the warehouses in that part of Baltimore. Progressive Field resembles the many bridges that cross the Cuyahoga River that runs by the park. The exterior of Nationals Park looks quite like a monument or Federal building.

Marlins Park looks nothing like Little Havana.

But I think the fact this exact structure could’ve been built in downtown Miami or, if necessary, the parking lot of Sun Life Stadium, isn’t a bad thing at all. What makes it work is that it says “Miami” … just as everything about the facility does.

The one unmistakable aspect of the shell of Marlins Park that is reliant on its location is the moveable “windows” beyond left field. That’s so you can see the downtown skyline, just over two miles to the east.

|

In case you haven’t figured it out by now, there is nothing about the park’s exterior that could be termed “retro.” Not one single aspect. Not one red brick. Not one beam of exposed steel that has been painted green. No old-time gates at the entryways. And if you think the seats on the inside are ubiquitous dark green, well, you are sadly mistaken.

To the contrary, Miami’s new showplace is modern in almost every respect.

Loria told the Miami Herald about an early meeting with the Populous design team. The Marlins owner told the designers that it was OK to “look back” to a limited degree, but the most important thing is ” to look forward, so I want you to come back to me with some contemporary drawings that are circular and glass and steel.”

Rather than limiting the designers, they felt liberated, according to Sherlock. They viewed the stadium as “an abstract interpretation of Miami, as art.” This was evidenced in “the fluid forms, pure white, reflectivity, shelter, tropical landscape (and) portals of color” that mimic what he calls “the Miami experience.”

Is Loria, who made his fortune as an art dealer, happy with the non-retro design produced by Populous? “They nailed it. It was perfect.”

Let’s examine the stadium’s outermost structures first. At each corner of the rectangular site is an immense parking garage. There’s a certain symmetry to the four of them, as they appear to anchor the much-taller stadium at the center. If the stadium weren’t as tall, the garages would prevent you from seeing the ballpark at all from the main east-west route, NW 7th Street, which runs along the north side of the site.

When they were constructing the garages, they left space on the ground floor that can be developed into retail stores or eateries. If such businesses do open one day, one has to wonder where their customers will come from when there is no game that day.

|

The space between the garages and the stadium has been fashioned into walkways with pleasant landscaping, although the one along the southern edge of the ballpark looks into loading docks, so it’s not nearly as scenic as the one on the north (this is the north side, above left).

On the east end of the ballpark — the one closest to downtown — there is a large entry plaza with a form of art embedded in its concrete floor. The idea was to memorialize the football stadium that once stood on this site. Above each end zone were large orange letters that spelled out MIAMI ORANGE BOWL. Those 15 letters can now be found in random fashion on the plaza, as if this is where they fell when the old stadium was demolished (above right).

At the northeast and southeast corners of the stadium are long, curving entry stairways that take you up to the main concourse. In between is the outer portion of the night-club part of the ballpark. The Clevelander (left side below) is an ultra-hip hotel and club in Miami Beach, and that vibe is reproduced in its ballpark counterpart that stretches from the left-field fence of the playing field to a roped off outer porch that is actually outside the stadium itself. Above the Clevelander are the towering windows that allow fans in their seats to see the downtown skyline.

As elaborate as this eastern end of Marlin Park might be, that’s only the appetizer. The main course is the West Plaza, on the opposite end. This is envisioned as the gathering spot where fans will congregate prior to a game. This is where the two main ticket windows are located, as well as the outer retail store.

|

But this is no ordinary plaza. The Marlins like to point out that it is the size of three-and-a-half football fields, with its own work of art acting as walkways. Venezuelan artist Carlos Cruz-Diez created the colorful patterns that change hue depending on your perspective and the amount of surrounding light (above right). One of the stadium’s three high-res video screens is located at the south end of the plaza (see right-hand shot below; the other two screens, of course, are located above the field inside). Team literature about the ballpark notes that this video board is meant to “contribute to the interactive environment of the West Plaza before and after games.”

And perhaps most special of all is what is above this area. When the retractable roof is open inside the park, the roof panels are “parked” at the west end of the facility. These panels form “a canopy which celebrates the West Plaza as the front door” of the stadium, according to Sherlock. Indeed, these panels completely cover the plaza, creating what Sherlock calls “a monumental civic garden in the city, unique to anything else in the world.”

|

| The West Plaza has a completely different feel when the retractable roof is open inside (meaning the roof panels cover the outside plaza) versus when those panels are covering the field, leaving the plaza exposed. |

As far as I could tell, there is only one place where you can sneak outside the ballpark from the inside, and re-enter without having to show your ticket. As you can imagine, this balcony is pretty much the domain of smokers, since you can’t light up anywhere inside the stadium. Since this is technically part of the exterior of the facility, we’re mentioning it here. This terrace (below left) is next to the Fan Feast concession stand off the main “Promenade” concourse near the retractable windows. And, yes, when you combine the view from here with the tobacco smoke, it is indeed breathtaking.

|

The only ramps in the entire complex are located at the south end of the West Plaza (see the center of the right-hand photo above). However, they aren’t circular like at Kauffman Stadium or Sun Life Stadium, nor are they parallel like almost every other MLB park in the land. No, these ramps form a triangle — all part of the ingenious geometry of Marlins Park. “The building geometry is a series of forms derived from angles, reinforced to visually connect outside with inside,” and vice versa, says Sherlock. “This basically creates visual movement pointing the eye toward the city skyline, the fundamental organizational principle” of the entire design of the ballpark.

And it works.

So let’s see how this geometry works inside the park, as well as on top of it.