Article and all photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

FAYETTEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA One of my greatest thrills in sports was attending the Major League Baseball game held in a temporary stadium at Fort Bragg during the 4th of July weekend in 2016.

| Ballpark Stats |

|

| Team: Fayetteville Woodpeckers of the High-A Carolina League |

| First game: April 18, 2019, a 7-5 loss to the Carolina Mudcats |

| Capacity: 5,252, of which 3,596 are fixed seats |

| Dimensions: LF – 340; LCF – 368; CF – 400; RCF – 357; RF – 325. |

| Architect: Populous. Lead Project Designer – Mike Sabatini; Lead Project Architect – Aaron Noll |

| Construction: Barton Malow |

| Price: $40.2 million |

| Home dugout: 1B side |

| Field points: Northeast |

| Playing surface: Latitude 36 Bermudagrass |

| Naming rights: purchased by Segra, a broadband service provider |

| Ticket info: www.milb.com/fayetteville/tickets |

| Betcha didn’t know: The predominate colors in the ballpark are red, gray and black, which match the official colors of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command at nearby Fort Bragg |

I covered the event for USA TODAY, and they ran my piece on the USATODAY.com website. I gathered so much material that I posted a multi-article series previewing the event here on Baseballparks.com. Part 1 is here.

I was so blown away by the success of this “pop-up park” that I wrote this review of Fort Bragg Ballpark and named it our Ballpark of the Year.

The reason MLB wanted to go to this trouble and expense is tied to why the event was so impactful to me. The folks at baseball HQ in New York wanted to honor the brave men and women who serve our country by bringing a big-league game to their backyard. Indeed, Fort Bragg is the largest military installation in the U.S., housing over 50,000 soldiers.

In addition to the game representing a series of “firsts” (first MLB game at a military base; first time a temporary ballpark was constructed for a big-league game; first regular season MLB game in North Carolina), it allowed me to get an up-close feel for the lives of those living and serving at Fort Bragg.

The sense of honor and service that was obvious in each member of the military whom I interviewed had a huge effect on me. While it was us who should be showing our appreciation to them, they kept telling me how much they appreciated that the game had been brought to them, and the way they were being honored.

I’ve gotten to attend some big baseball events, but none made a bigger impact on me than that evening.

The closest city to Fort Bragg is Fayetteville. I didn’t realize it at the time of the Fort Bragg Game in 2016, but in some ways, that game was sowing the seeds for pro baseball to come to that city in southeast North Carolina. And when it would come back, the military would make a major impact on the new team.

During that wildly patriotic July 4th weekend in 2016, some major developments were being finalized within the workings of Minor League Baseball.

Two teams in the California League were in terrible shape, and were hanging on by a thread. The Bakersfield Blaze was playing in the worst facility in the affiliated Minors, and the High Desert Mavericks’ park in Adelanto, CA wasn’t much better. Attendance was awful at both venues, but even more importantly, Major League clubs were pleading for their high-A teams to be in the East, not playing in substandard facilities on the West Coast.

| Not the only Segra |

|

| Just like a number of banks (PNC, BB&T, Fifth Third), tech company Segra has its name on multiple ballparks. The Columbia Fireflies’ park used to be Spirit Communications Park, but after Spirit and Lumos merged to form Segra, the facility is now known as Segra Park. |

Minor League Baseball decided to “contract” two teams from the California League and add two in the Carolina League. The Major League teams who benefited from this were the Rangers, whose young players had been assigned to High Desert, and the Astros, who had been affiliated with Lancaster since 2009, but desperately wanted their high-A team to be back east. Those two big-league clubs would end up owning those new Carolina League franchises (which was not the case in California), and they both wanted their new clubs in North Carolina.

Six weeks after the Fort Bragg Game, Minor League Baseball announced the series of moves. Bakersfield and High Desert would henceforth be out of affiliated pro baseball, and Kinston and Fayetteville would be the recipients of the new Carolina League franchises.

The Rangers and Astros went about things in radically different ways. The former selected Kinston because it already had a park that was suitable for high-A baseball. In fact, Grainger Stadium had been the home of a Carolina League squad until 2011, when it shifted 65 miles northwest to Zebulon, NC.

The Astros, though, desired a brand-new ballpark. One certainly couldn’t be built in the few months from the announcement in August, 2016 to opening day of 2017, so they arrived at a short-term and long-term solution. In the long run, the Astros would work with the City of Fayetteville on building a new park. In the meantime, though, they would commit to two seasons at a college ballpark in Buies Creek, sharing the field with the Campbell University Camels. Since it was only 30 miles from Fayetteville, the Astros could establish an office there and start to sell tickets. They would also be close to the construction of the new stadium.

The Rangers had what they wanted, and so did the Astros — although the latter had to go to considerable effort to bring their forever home online.

It was a beautiful evening on April 18, 2019 when the Fayetteville Woodpeckers took the field for the first time in their new home, a ballpark called Segra Stadium. The first pitch in the park is shown at the top of this page.

And it’s not an exaggeration to say that a community has never been as excited to land a Minor League team as Fayetteville. It seemed every establishment in town had signs out front welcoming the team and having Woodpeckers Specials on food and drink.

| Talk about being excited! |

|

| Is Fayetteville going nuts over their new team and new park? Here’s evidence that the answer is a resounding YES. |

|

More telling, though, was the Fayetteville Observer, the City’s daily newspaper. The day before the first game, the headline over the Observer‘s lead story on the front page was Thursday’s home opener is sold out. The day of the first game, it was Excitement as opening day arrives. The morning following opening night, almost the entire front page of the paper was devoted to the big event. The only headline on the page was PLAY BALL in bold inch-and-a-half-tall type (see photo).

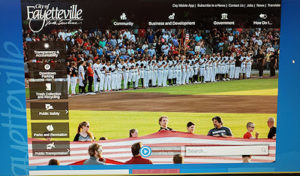

Not only that, when I took a look at the official website for the City, the home page had a huge picture from Opening Night. I’ve never seen this level of civic pride in the arrival of Minor League Baseball.

“I heard a number of people say in relation to the stadium, ‘Fayetteville deserves this,'” observed Kristoff Bauer, the Deputy City Manager. “We have a bit of an inferiority complex and tend to be looked down upon by other regions of the state. This is about making the statement that Fayetteville is in no way ‘lessor than.’ We are the sixth largest city in the ninth largest state in the greatest country in the world. We deserve a stadium fitting for a community of this stature.”

Woodpeckers President Mark Zarthar came up with these analogies for how important the ballpark is to Fayetteville: “This stadium is the Central Park or Golden Gate Bridge of Fayetteville.” Proof? “We’re essentially running ahead of all of the benchmarks we set on ticket sales, retail sales and sponsorship sales.”

When I asked Astros Owner Jim Crane why Fayetteville was selected, he referenced the Fort Bragg Game. “One of our themes is the military. We are really behind the military. (MLB) played a game here, so we thought this would be a great place to interact with the military and keep with our theme.”

“What’s great about baseball is that it brings a community together,” Astros President of Business Operations Reid Ryan told me. “And this ballpark is going to bring this community together from the aspect of the military and its retirees to those people who work here in town.”

And needless to say, the military presence is vitally important to the City. “Fort Bragg and the Department of Defense are 48% of the local economy, but more importantly the military is a substantial part of the fabric of our community,” said Bauer. “Active duty, veterans, and their families not only make up a huge portion of the people we serve, they are also our employees and our community and elected leaders.”

Let’s look deeper into why Fayetteville was chosen and what trade-offs occurred in the site selection. Then we’ll examine the park’s architecture and what attending a game at Segra Stadium is like.

The Setting

Before we address the 800-pound gorilla in the room regarding the setting of this ballpark (that is, its lack of visibility), let’s look at why Fayetteville is the recipient of this coveted franchise.

The Astros and Rangers essentially bought the new Carolina League franchises so the owners of the contracted Bakersfield and High Desert teams could be compensated. The Astros were eager to do that “because our players and their development are our top priority, and having all of our affiliates as close as possible geogaphically was important,” Zarthar explained. “And being in the same time zones was important, so California was a challenge. There are no High-A leagues in Texas or the Midwest, so the Carolina League was a fair compromise.”

| The faces of the franchise |

|

| Mark Zarthar (left) was brought in by the Astros to be President of the Woodpeckers. Victoria Huggins is the Manager of Community and Media Relations. The former Miss North Carolina is from “30 minutes down the road in St. Pauls — two stop lights and a Piggly Wiggly.” |

In looking for a specific city for their team, the Astros “pinpointed a market that would best facilitate our needs and best facilitate a quality fan experience. What stood out about Fayetteville was that they were passionate about bringing a Minor League Stadium to the downtown.”

Zarthar related how several decades ago, downtown Fayetteville offered entertainment that “wasn’t conducive to a family friendly environment” to cater to the servicemen at Fort Bragg. “When I was growing up here, I was told never to go to Hay Street by myself,” added local native Victoria Huggins, the team’s Manager of Community and Media Relations.

The City “made drastic changes to improve downtown and to welcome families with dining and culture and art,” said Zarthar. “It became time for Fayetteville to take that next step to provide downtown with a shot in the arm, to boost economic impact and to bring more people downtown.” That step, of course, is the new ballpark. And it’s situated near the same Hay Street neighborhood that Huggins was warned not to wander into when she was younger.

Today’s Hay Street is a far cry from decades past. Adorable shops, restaurants and galleries dot the City’s main thoroughfare. They deserve the additional foot traffic that having a baseball game 70 times a year can bring.

|

| Gone from the Historic District are the strip clubs and bars of decades gone by. The quaint shops and outstanding eateries are now decidedly family friendly. |

While the positioning of the ballpark on the chosen plot of land is, well, odd, overall the site is wonderful. It’s at the western edge of the town’s historic district, within easy walking distance of dozens of those picturesque establishments.

Near the park are some interesting points of interest. A short walk to the north is Festival Park, a lovely public gathering spot complete with a stage for outdoor concerts and civic events. Its proximity to the ballpark means that for big events — like a 4th of July celebration — the stadium could become an extension of Festival Park.

|

| Like in North Augusta, there is a lovely public park just north of the baseball stadium. Festival Park in Fayetteville lacks the swamps and mosquitoes of Brick Pond Park in North Augusta, though. By the way, the bridge shown in the first photo above leads to a path that ends up at the ballpark. |

A block west of Segra Stadium is the impressive U.S Army Airborne and Special Operations Museum. Amazingly, admission is free. It is well worth your while.

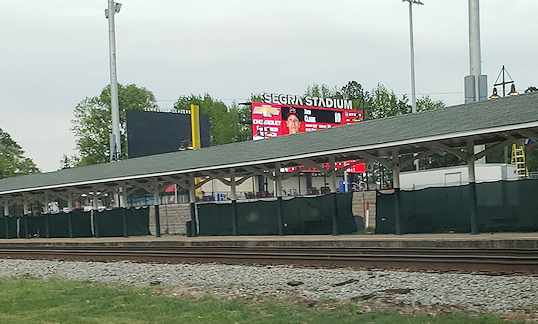

Just across Hay Street from the ballpark site is City Hall. Adjacent to the park is the Fayetteville Amtrak Station. David Bower, Principal at Populous, the architects behind the stadium’s design, remarked that it’s hard to overstate “the value of that depot to the City and to (Fort Bragg). You can just see all of the soldiers standing there, waiting to go to their enlistment stations.”

This was taken from the west side of the train tracks, looking though the station’s platform toward the ballpark’s video board. This was taken from the west side of the train tracks, looking though the station’s platform toward the ballpark’s video board. |

How close is the station to the ballpark? “If you are standing on that platform waiting for a train, you are literally a guardrail away from the concourse of the ballpark. Thankfully,” Bower added, “we were able to keep all of that platform and still fit the ballpark in.”

I’m also thankful that the proximity of the depot didn’t tempt any of the Populous designers to push for a train-station theme for the ballpark, because that’s been overdone.

|

| These shots show the City-owned parking lots before construction began on Segra Stadium. The first photo shows the train station in the distance. The second shot is looking north, toward Festival Park. |

Initially, the City considered other parcels of land “that may have had more street prominence, but they were distant from the City center and would not have attracted the adjacent private development available at this location,” noted Bauer. Populous wasn’t enamored by any those other locations, either. So the focus switched to City-owned parking lots that Bauer said were “under-utilized” close to Hay Street. Adds Bower, “We were really delighted when the City said ‘Hey, we want you to check out this other site.'”

That other site, though, wasn’t without its challenges. It had the train station in one corner, an abandoned, deteriorating hotel in another corner, and was bounded by train tracks on two sides. I’m sure there was talk of demolishing the old Prince Charles Hotel to allow the ballpark to sit right on Hay Street — but then a proposal came through to retain the hotel and turn it into luxury apartments. In fact, the man behind the purchase and re-purposing of the Prince Charles, Jordan Jones, is the great-great grandson of the man who built the hotel in 1925. Jones and his investors have poured $18 million into converting the hotel rooms into apartments.

| Name clarification |

| Two individuals quoted in this article have very similar last names. In fact, the pronunciations are identical. When we’re quoting Bauer, it’s Kristoff Bauer of the City of Fayettville. When there’s a quote from Bower, it’s David Bower of the architecture firm Populous. |

Keeping that building meant that “there wasn’t enough room to squeeze the ballpark between the hotel and the train depot,” Bower recalled. “As we slid the (the park) farther and farther from Hay Street, they were able to fit another new hotel in and to permit a view corridor from the street to the entrance of the ballpark.”

So in the end, what would have been a fairly straightforward placement of the ballpark right on Hay Street turned into a pretty crowded arrangement. The re-purposed Prince Charles and a to-be-built structure containing retail space, a parking garage and a Hyatt Place Hotel were all to sit right on Hay Street. The stadium had been pushed to the north about 150 feet, leaving fans to walk through a long, narrow entry plaza to get to the ballpark’s gates.

The unintended consequence of that distance is the lack of visibility the very pretty ballpark has from traffic on Hay Street. This bothers me. A lot. It reminds me of the poor site selection of First Tennessee Park in Nashville, which is a block to the south of Jefferson Street, the main thoroughfare that runs through that area. In both cities, you can drive along the main street and not realize a ballpark that cost tens of millions of dollars is nearby.

Hours before Segra Stadium’s opening game, this was the scene looking across Hay Street into the “view corridor” between the Prince Charles Hotel on the right and the construction site (that will be retail, parking garage and Hyatt Place Hotel) on the left. Hours before Segra Stadium’s opening game, this was the scene looking across Hay Street into the “view corridor” between the Prince Charles Hotel on the right and the construction site (that will be retail, parking garage and Hyatt Place Hotel) on the left. |

But we need to realize that there were trade-offs involved — and without the projected revenue from the renovation of the Prince Charles and the Hyatt Place/parking garage/retail space, there might not have been a ballpark at all. “The location is unique and I like to think we made the best of it,” explained Bauer. “The deal to construct the stadium was supported by the a commitment of $65 million in private economic development adjacent to the stadium.

“This project was not just about baseball. It was also about bringing jobs and residents to the downtown,” Bauer concluded.

One last aspect of the site needs to be examined: parking.

There’s a certain irony that “under-utilized” parking lots were eliminated so the ballpark could be built, because now you could argue that there aren’t enough parking spaces close to the park. And don’t think that the parking garage currently under construction adjacent to the main entry of the park will help. It won’t, as it will strictly be for the Hyatt Place and residents in the renovated Prince Charles.

When I arrived in town, I asked a helpful local who worked at City Hall where I should park for the Opening Day game. She said the clear choice was the parking garage at the corner of Franklin and Donaldson Streets — so that’s what I did. It was exactly a third-of-a-mile walk to the ballpark’s entrance. It was a nice day, and I didn’t mind — and I ate at the delightful Antonella’s Ristorante I passed on the way to the ballpark.

That third of a mile seemed a lot longer and a whole lot darker when I walked back to my car following the night game.

Bower noted that no new parking was added due to the arrival of the ballpark. He explained that Populous and the City assessed the availability of parking and found there was a sufficient amount within a quarter mile of the park. And he added with a smile, “And guess what, you’ll have all those people walking through the downtown past all those stores and restaurants on their way to the ballpark. From a community planning perspective, that’s perfect.”

Adds Huggins, “Fayetteville doesn’t have a parking problem. Fayetteville has a walking problem, because people complain about walking a quarter mile.”

I remember how fans were negative about the Braves’ SunTrust Park when it opened in 2017 — not because the park lacked amenities (because it assuredly doesn’t), but because of traffic and parking hassles. I don’t want Segra Stadium to be painted with the same broad brush.

I will make a suggestion to the Woodpeckers, though: consider running a van or shuttle from the ballpark to the Franklin Street parking garage following night games so fans won’t have to make that dark trek on foot.

The Exterior

The brick wall above greets every fan who enters Segra Stadium, because it’s adjacent to the main — and only — entryway.

| Architects +1 |

|

| The team from Populous was joined by a new friend. From left: Cameron Carver; Mike Sabatini; the cleverly named mascot Bunker; Steve Caudle; Aaron Noll. |

You probably don’t realize it, but this wall communicates a great deal about the ballpark:

- The nod to “victory” is a direct reference to the military at Fort Bragg, says Populous’ Aaron Noll, Lead Project Architect of the park;

- The shades of paint used are the colors of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg. They show up all around the ballpark;

- The map highlights the part of North Carolina where Fayetteville is located. “No matter how you look at it,” Huggins asserted, “the whole area of southeastern North Carolina knows that we have this $40.2 million facility here;”

- And you can’t see it, but this is one of several walls at the park that’s shared with the development under construction behind it. That’s how close the stadium and the retail/garage/hotel are to each other. Yes, it’s a tight fit.

And “tight fit” can be used to describe quite a bit about Segra Stadium. Says the Astros’ Reid Ryan, “We’ve taken this funky piece of land and we’ve been able to fit the stadium in here.” He added, “I think it makes it all the better because fans are going to appreciate what was here before and what’s here now.”

And what’s here now is a ballpark that is very much a product of its close quarters. In this respect, it reminds me of two other Populous projects: Target Field in Minneapolis and Southwest University Park in El Paso. In both instances, it’s a miracle that top-notch baseball parks are wedged into their sites.

Because of the parking garage behind home plate, the Amtrak platform behind third base and the freight-train tracks that run diagonally beyond the right field and center-field perimeter of the ballpark, Segra Stadium arguably has less “exterior” than any recently built pro ballpark.

In fact, the outside of the park that you see in the photo below is pretty much the entirety of the park’s exterior, not counting iron fencing that runs all around the outfield.

This is essentially all of the ballpark’s exterior. It’s quite pretty though, and the pad for military vehicles was a great idea. This is essentially all of the ballpark’s exterior. It’s quite pretty though, and the pad for military vehicles was a great idea. |

What the exterior lacks in length it makes up for in beauty. The brickwork is excellent, and the sole entry point of the park (shown in different ways below) is both stately and attractive.

|

| On opening day, fans were lined up in what will be an entry plaza once all of the construction is complete. In the first picture, the parking garage (that won’t be used for ballgame parking) is on the left. In the other image, stately columns hold up the roof above the space between the metal detectors and the main concourse. The windows on the second level are for the AEVEX Veterans Club, which shows good planning by the architects. |

This almost had a completely different look. “At one point early in the design, the parking garage was underneath the ballpark and the hotel and residential were directly on top of the ballpark,” Noll divulged. One assumes that this would have given the stadium much greater visibility as it might have been closer to Hay Street, although it would’ve had a radically different appearance.

As planning progressed on the single-structure concept, “it became a very complicated process because the ballpark was moving much faster than the hotel, so they ended up being separate.” Bower recalled. The two structures, however, “are pushed right up against each other with common walls.”

With the perimeter of the park being bounded by train tracks, there aren’t too many options for additional entryways. However, on the southeast corner of the stadium near the right-field foul pole is an opening that could be used as an entry gate. It features a ramp leading down to the playing surface (that was used for construction and today allows an 18-wheeler to bring a stage and amps down to the field for a concert) as well as a gap in the fence for fans to exit.

There’s a sign that calls this the Right Field Gate, but it wasn’t set up with metal-detectors or ticket takers. There’s a sign that calls this the Right Field Gate, but it wasn’t set up with metal-detectors or ticket takers. |

The line getting through the metal detectors at the stadium’s only entry was very, very long on opening night, so thought might be given to utilizing this opening in the fencing as another entry gate. It will certainly be the way revelers will access Healy’s bar in the right-field corner on non-game days.

But more on that as we venture inside the park, so read on!