Article and photos by Joe Mock, BaseballParks.com

All rights reserved

PATERSON, New Jersey For over a decade as he was growing up, Brian LoPinto lived over a small store in a working-class neighborhood of Paterson, New Jersey. This modest home was just two blocks from Hinchliffe Stadium, the city’s venue for much of the athletic endeavors at the time.

| Ballpark Stats |

|

| Team: New Jersey Jackals of the indy Frontier League |

| First game: May 21, 2023, a 10-6 win over the Sussex County Miners |

| Capacity: 10,000 — including 7,800 bench seats in seating bowl |

| Dimensions: LF – 320′; CF – 385′; RF – 327′ |

| Fence heights: LF – 7′; CF – 12′; RF – 40′ |

| Developers: RPM Community and BAW Development |

| Architect: Clarke Caton Hintz |

| Construction: Pike Construction of Paterson |

| Price: $30 million, part of $103 million project |

| Home dugout: 1B side |

| Field points: south |

| Playing surface: artificial, made by FieldTurf |

| Named for: John Hinchliffe, Paterson mayor 1929-37 |

| Ticket info: jackals.com/promos |

| Betcha didn’t know: Hinchliffe is the only ballpark located within a U.S. National Park |

As a teenager, LoPinto’s family moved to nearby Clifton. As a baseball player at Clifton High School, he played Paterson’s high schools four times at Hinchliffe.

While in college in 1997, he read the unsettling news that the venerable stadium had fallen into such disrepair that it had been condemned. “Growing up in the neighborhood, I would look at the stadium and think, ‘this had to have been used for more than high school games,'” he told us.

So he made it his mission to research the facility’s background. He referred to the 1992 book Green Cathedrals, written by Philip Lowry. Right there at the bottom of page 203 was a passing reference to Hinchliffe. In addition to noting that it opened in 1932, it mentioned that the New York Black Yankees of the Negro National League played there from 1936 through 1945.

This prompted LoPinto to send a letter to the Hall of Fame to see what he could learn, and they sent him a nice response. “This encouraged me to do even more research, so I started spending a lot of time at the Paterson Library, going through microfilm. I read about all of the great Negro Leaguers who’d played here.”

Very significantly, Larry Doby grew up in Paterson. He wasn’t just a run-of-the-mill Negro Leaguer.

Everyone knows the name Jackie Robinson and what he accomplished in breaking MLB’s “color barrier” in 1947. Not enough fans know the name Larry Doby, and that’s a shame. After being a star athlete in four different sports while at Paterson’s Eastside High School, he signed with the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League — with his tryout taking place at Hinchliffe. After a stint in the Navy during World War II, he returned to the Eagles to lead them to the 1946 Negro League World Series title.

Then three months after Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Doby became the Majors’ second Black player, signing with the Cleveland Indians. He spent no time in the Minors, going directly to the big club, and he and Satchel Paige helped the Indians win the 1948 World Series. Thirty years later, Doby would become only the second Black manager in the Majors.

“His place in baseball history was just as significant as Jackie Robinson, and in many ways, maybe more so,” noted Negro League Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick on his Black Diamonds podcast.

Doby was just one of many spectacularly talented Negro League players who took the field at Hinchliffe. “It was like a piece of Cooperstown was right here in Paterson because of all of the great players who had played here,” LoPinto noted. “I was very pleased that my hunch had substance that Hinchliffe was more than a high school stadium.”

But he feared that the clock was ticking toward the inevitable demolition of the condemned facility.

| Founder of Friends |

|

| Brian LoPinto, shown on the right with me, helped form the Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium, which was instrumental in saving the historic ballpark from the wrecking ball. |

In 2002, he heard about a lecture outlining a vision of what could be done with Hinchliffe. The presenter was civil engineer Christopher Coke. LoPinto attended and told Coke of his own interest in the decaying landmark. The two of them joined forces with Dr. Flavia Alaya, professor emeritus at Ramapo College, to form The Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium. This non-profit organization was able to raise awareness — and just as importantly, money — to try to preserve the crumbling stadium. “Our first goal, though, was simply to prevent its demolition,” said LoPinto.

In 2009, the fledgling organization reached out to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, “because our research showed Hinchliffe had national significance,” LoPinto explained. The Trust agreed to place the stadium in a pilot program called “National Treasures.” That designation provided Hinchliffe with $300,000 in funding. Thereafter, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places and, eventually, was officially named a Historic Landmark.

The momentum to save the stadium was building.

The Friends of Hinchliffe were successful in obtaining a matching grant of $500,000 from the New Jersey Historic Trust in 2011. This was great news … until you stop to realize that the Friends had to come up with $500,000 on their own to obtain the matching funds. “Since the Board of Education owned the property, we worked very closely with the City Government and the Board to raise the funds. Thankfully, the City had some funds that were available for such purposes,” LoPinto said.

With $1 million to work with, the first stage of renovations could begin. In 2013, the outer wall on the northwest side of the stadium along Liberty Street was rebuilt to its original glory. It was only a start, “but it showed it could be done.”

As we’ll see in the next section, the City of Paterson and its mayor made the total renovation of Hinchliffe a high priority. Earlier this year, a project costing $103 million was completed on a single parcel of land that includes, as we will see, four elements, one of which was the rebuilt Hinchliffe Stadium.

Read on to learn about the stadium’s fascinating surroundings, and what it’s like attending a ballgame here.

The Setting

“When African Americans couldn’t play in Major League Baseball, they had a home at Hinchliffe Stadium.”

That poignant point was made to us by Paterson Mayor Andre Sayegh. He pointed out that the year following the opening of Hinchliffe in 1932, the New York Black Yankees played a game dubbed The Colored Championship of the Nation in Paterson. Initially an independent team, the Black Yankees joined the Negro National League in 1935. Over the next decade, they played home games at a variety of venues, including Hinchliffe, Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds.

| 14-year journey |

|

| Andre Sayegh was elected mayor of Paterson in 2018, but he began “a 14-year journey” to preserve Hinchliffe in 2009. |

In 1935 and ’36, another team from the Negro National League, the New York Cubans, also played home contests at Hinchliffe.

“The stadium’s significance is that it tells the story of social justice, equality (and) civil rights,” Sayegh added.

“The rebirth of this stadium also signaled the rebirth of our city. Paterson has taken its share of losses, but bringing back historic Hinchliffe Stadium puts Paterson back in the win column.”

The mayor couldn’t resist comparing the ballpark to another famous facility in the Midwest. “This is America’s true ‘field of dreams.’ With all due respect to Iowa’s cornfield, that was a movie set. Legends played on this field. That’s why we need to celebrate it.”

He stresses that it wasn’t easy accomplishing the rebuilding of Hinchliffe. “This has been a 14-year journey. I was a (city) councilman back in 2009, and I said I’m tired of passing by this significant stadium and seeing it in decay. It was an eyesore.” He noted that adding to the unfortunate nature of the situation was that students at the adjacent school had to see the deteriorating facility every time they looked out of the windows. “They saw trees growing up in the stands, vandalism (and) homeless individuals living in the locker rooms.”

| Towering over Paterson |

|

| Another landmark in Paterson is the Lambert Tower, part of Garret Mountain Reservation. There are wonderful views of Paterson from this mountain top. |

In 2009, Sayegh and his wife traveled to Birmingham to see how that city had been successful in maintaining historic Rickwood Field, also the home of Negro League baseball. He decided that he lacked the clout to bring about the rebuilding of Hinchliffe as a councilman, so he ran for mayor. After losing twice, he was successful in 2018.

Despite opposition from others who wanted dollars spent on different projects in Paterson, he pushed to have funds at his discretion used to rebuild the stadium. He refers to these dollars from the State of New Jersey as “tax credits to incentivize investment in urban centers.”

But Sayegh had bigger plans than just the stadium, as he included a new senior-housing facility, parking garage and a building to house a Negro Leagues museum in the project that included the stadium. All told, it was a $103 million expenditure. The mayor refers to this as “neighborhood revitalization.”

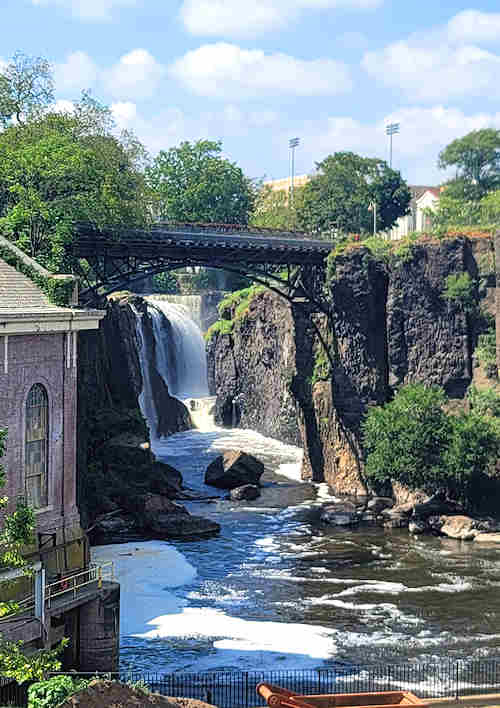

A significant event in the timeline occurred in 2015 when New Jersey Congressman Bill Pascrell — who likes to call himself “a native son of Paterson” — fought in the U.S. House of Representatives to have Hinchliffe included within the boundary of the Paterson Great Falls National Historic Park. That Park had just received its status as a “historic park” in 2009, and in 2011 was officially accepted by the U.S. Department of the Interior to be managed as a national park. When its boundary was expanded to include Hinchliffe, it provided additional protections — and money — to prevent the stadium’s demolition.

And you simply can’t discuss Hinchliffe Stadium without mentioning the Great Falls just beyond the ballpark’s outfield. The falls in the Passaic River send water crashing 77 feet into a gorge, creating not only a very impressive sight, but a historic one. You see, as far back as Alexander Hamilton, the rushing water was harnessed to power mills and the machines of industry — and later, hydro-electric power.

The city of Paterson was established because of Hamilton’s vision of a “national manufactory” at the site of the falls. The fact that Hinchliffe is right up the hill from these falls is a happy coincidence. In fact, the entrance to Mary Ellen Kramer Park, which is on the uphill side of the falls, is just a few feet from the southwest corner of the rebuilt ballpark (see below).

I was surprised to learn that Paterson’s population of 159,419 is the third largest in New Jersey, trailing only Newark and Jersey City. And while the scenes of its inner city lack the Midwestern charm of Oconomowoc, Wisconsin (see our review of the Lake Country Dock Hounds’ park and surroundings here), it more than makes up for it in its fascinating ethnic diversity.

Truly this is a city worth visiting, not only to see the historic stadium, but also to experience its incredible ethnic neighborhoods … and restaurants!

One example of this is Palestine Way — also called Little Palestine — on the southern end of town, emanating out from the intersection of Gould Street and Main Street. There are so many Middle Eastern restaurants here that you can’t count them all. And best of all are the bakeries filled with freshly baked treats.

|

Closer to the Falls is bustling Peru Square, sometimes called Little Lima, with Peruvian eateries and merchants. Add to these the Italian and Dominican communities in Paterson, and you know you’ll need to come hungry when you visit the city.

But even with a historic stadium being rebuilt and a fascinating city surrounding it, there was a problem: there was no baseball team to play in the newly renovated Hinchliffe. Mayor Sayegh, of course, had a solution. “Al Dorso, the owner of the New Jersey Jackals, and I met at a diner in 2017. I told him that if I’m elected mayor, my top priority is to restore Hinchliffe Stadium, and I want you to bring the Jackals to Paterson. He sort of brushed aside that notion. But we were persistent.

“And just like in Field of Dreams, if you build it, he will come.”

On September 14, 2022, it happened — and Ray Liotta was nowhere in sight. The Jackals of the independent Frontier League (which is a “partner league” of MLB) indeed announced that they were moving the franchise to Hinchliffe for the 2023 season. In so doing, they were leaving their home for the past quarter of century, Yogi Berra Stadium on the campus of Montclair State University in Little Falls, New Jersey.

| It ain’t over ’til it’s over |

|

| Yogi Berra Stadium was the Jackals’ home for 25 seasons. At the extreme right in this photo is the entrance to the Yogi Berra Museum, which is definitely worth visiting. |

Dorso, you see, was born and raised in Paterson. On the day of the announcement, he said, “Even though I ventured on, I still know this town like the back of my hand and have many fond memories.” He added that he was anxious to “give back and add to the rich history of the region.”

When I had attended a Jackals game at Yogi Berra Stadium, I had no idea that I was so close to a ballpark with such a rich Negro League history. The distance between the two? Five miles, or a ten-minute car ride.

Paterson, by the way, is a scant ten miles from mid-town Manhattan. In fact, when the weather cooperates, you can see the skyline of New York City from the seats behind first base in Hinchliffe. That is pretty cool. To accomplish that, you have to look beyond the picturesque steeples and rooftops of Paterson, as shown in the photo at the top of this section.

While it would take some work, Major League Baseball should seriously consider playing a “Field of Dreams” game here. For all of the reasons that make the June 2024 game at Birmingham’s historic Rickwood Field a good idea (Negro League baseball was played there, it will honor Birmingham native Willie Mays), Hinchliffe should be awarded the same honor. After all, it’s the only park other than Rickwood that’s still standing that regularly hosted the Negro Leagues, plus such a game could honor Paterson’s Larry Doby.

“Yes! That’s our goal,” said Sayegh. “We need everyone at bat, and hitting a home run for Hinchliffe Stadium to get that game.”

Make it happen, MLB! And consider this: there have been no MLB games played in New Jersey since the Brooklyn Dodgers played a handful of weekday games in Jersey City’s Roosevelt Stadium in 1956 and ’57.

Keep reading! Page 2 describes the exterior look of Hinchliffe, its interior design and what it’s like to attend a Jackals game. Don’t you want to know our choice as the best concession item?? Click below! And please make sure to leave a comment at the end of this review.