An edited version of this article appeared in the USA TODAY Spring Training Preview on Feb. 22, 2017. Many thanks to the editorial staff for permitting us to reproduce the unabridged version here. All photos shown here are by Joe Mock. All rights reserved.

By Joe Mock

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA “We know fans come here because it’s one big baseball theme park in Arizona every March,” says Michelle Streeter, VP of Communications for Visit Mesa, which promotes tourism to the city.

If baseball fans look at the Phoenix area’s 10 spring-training complexes as the sport’s Walt Disney World, then its Magic Kingdom has to be Salt River Fields at Talking Stick. The sprawling complex has been the springtime home of the Arizona Diamondbacks and Colorado Rockies since 2011.

If baseball fans look at the Phoenix area’s 10 spring-training complexes as the sport’s Walt Disney World, then its Magic Kingdom has to be Salt River Fields at Talking Stick. The sprawling complex has been the springtime home of the Arizona Diamondbacks and Colorado Rockies since 2011.

When Disney World opened in 1971, it revolutionized theme parks. Did Salt River Fields have the same impact on spring training? “I think it did,” says Dave Dunne, General Manager of Operations at Salt River. “It brought spring training to another level, a revolutionary level.”

Derrick Hall, the Diamondbacks’ President and CEO, doesn’t think it’s overstating the situation to use such terms. “No, not at all. That was the goal.” He added that the complex has been “revolutionary when you talk about design, architecture, shade, landscaping, parking, multi-use (capabilities) and player preparation.

“Some other new ballparks are great, but this one has touched every possible point and connected them.”

Adds Jeff Meyer, president of the Cactus League Association, “No question it set the bar higher for future spring-training facilities and what teams are looking for.”

TIPPING THE SCALES

The scale of Salt River Fields was unlike any spring-training complex previously built. The 140-acre site, which is in a Scottsdale zip code but not within its city limits, is on land controlled by the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, which funded the construction of the facility.

As Dunne likes to point out, before Salt River, “spring-training clubhouses used to be in the 30,000-to-40,000 square-foot range. Each team’s building here is 85,000.”

Kevin Kahn, the Rockies’ VP of Ballpark Operations, observed, “From a (player) development standpoint, Salt River allowed us to implement all of the things we’d talked about but couldn’t do in Tucson,” the team’s previous home. “For example, our weight room is two stories high with a cardio mezzanine on the upper level. Every spring, we had to rent a truck to take our weights from Denver to a tent in Tucson. Now our players can use the facilities at Salt River even in the offseason.”

POWER OF POSITIVE INFLUENCE

POWER OF POSITIVE INFLUENCE

Mo Stein, Principal at HKS, the architects of the complex, notes that “No one has ever gotten close to matching the scale we did at Salt River. Is it an influencer? Yes, it’s a big influencer.”

Hall noted that other teams who are contemplating new complexes or renovations to their existing facilities invariably come to Salt River for a tour. This has included representatives from several cities in Mexico. “It’s a big compliment that this has become the prototype, not only in spring training but also globally.”

Since Salt River opened, municipalities in Arizona like Surprise, Peoria and Mesa have spent millions of dollars in renovations and enlargements of exiting spring-training facilities. Complexes in Florida have also received huge upgrades, benefiting the Yankees, Twins and Tigers. Nick Gandy, the Florida Sports Foundation’s liaison for the Grapefruit League, recently toured the significant improvements in the Tigers’ facilities in Lakeland, including a new 85,000-square-foot clubhouse. “I knew that they’d toured all the parks in Florida and had also visited Arizona. I took one look at the clubhouse and said, ‘Are these ideas you got at Salt River?’”

Perhaps Salt Rivers’ biggest impact can be seen in the Cubs’ complex in Mesa, which opened in 2014. Not only was it built on the site of an old golf course, just like Salt River, the immense size of the clubhouse, two-story weight room, training rooms and even a theater are quite similar to those of the Diamondbacks and Rockies. And after seeing the crowds that Salt River could attract, Cubs Park (now dubbed Sloan Park), the Cubs’ stadium in Mesa, was built to be even bigger.

“Imitation is the best form of flattery,” adds Streeter. “Having visited Salt River Fields, there’s no question that it was taken into account when designing Sloan Park.”

In fact, Dunne notes that “the Cubs came through seven or eight times, which is great because we love showing the place off.”

FAN ACCESS

FAN ACCESS

Stein recalls how the process of designing Salt River Fields began. “I wanted to re-think spring training with two really forward-thinking teams. I wanted to re-invent the experience.” As discussions proceeded between HKS, the teams and the Indian Community, the parties agreed that there was but one goal: “to create the absolute ultimate fan experience. It was not to make it bigger or make it louder or make it prettier or do more than anyone else. It was (to) create the ultimate fan experience. Period.”

Hall recalls those early meetings were “focused on the fan experience, not only in the main stadium but around the practice facilities. It goes back to my time working for the Dodgers at Dodgertown (in Vero Beach), which I think was the cream of the crop. The fans were right in the middle of the action. They would walk with the players from the clubhouse to the field or from the field to the stadium. That’s what I wanted to create here. That was my main focus, and we were able to accomplish that.”

BIGGER CROWDS THAN EVER

And the fans have responded.

In 2010, the final year the Diamondbacks and Rockies trained in Tucson, the average crowds at their home exhibition games were 6,647 and 5,243, respectively. In the six springs since moving into Salt River Fields, the Diamondbacks have drawn an average of 11,060 while the Rockies have averaged 9,938.

Overall, Cactus League attendance has jumped quite a bit, thanks largely to Salt River and Sloan Park. In 2010 (the last year before Salt River opened), a total of 1,470,722 attended Cactus League games. Last year, the total was 1,884,150.

IMPACT ON PLAYERS

IMPACT ON PLAYERS

Do players feel like Salt River is a different experience for them?

Kahn recalls his conversations with Rockies players who played both at Hi Corbett Field in Tucson and Salt River. “They all say they were struck by the different feeling of having a full or almost-full house every game.”

And that experience, along with the wonderful facilities, has helped the D-backs sign free agents. “We’ve had our players tell us that one of the reasons they came here was because of Salt River Fields,” says Hall. “It has made a difference. It really has.”

Before Dunne came to Salt River, he oversaw operations at the Cubs’ previous spring home in Mesa. “It was a vision to one day have year-round activities. Now we have guys out here working out or practicing on the fields eleven-and-a-half months out of the year. They love it and they want to be here doing something. It’s really changed the mindset of a number of Major League organizations about how to use their spring-training facilities.”

“Salt River has been huge for us as a team to get better, to grow and learn the game,” said the Rockies’ star 3B Nolan Arenado. “My second spring training was when this place opened. It’s amazing what we are able to get done. (There are) so many things to make us a better baseball team. It’s truly been amazing.”

Players on the D-backs love the complex’s convenience. “The location of Salt River Fields is incredible,” former pitcher J.J. Putz observed. “The easy access for players to get to the stadium is ideal. It is right off the freeway so you can pretty much rent a house anywhere in the Valley and get there easily.”

PRIVATE MONEY

For the most part, public funds have constructed and renovated the complexes in Arizona. Not so with Salt River, which was built by the Indian Community. Although no figures have been made public, it’s estimated to have cost at least $120 million.

Mark Coronado has been the Parks & Recreation Director for the City of Surprise for the past 18 years. In that role, he was responsible for overseeing $32 million in renovations to the Rangers’ and Royals’ clubhouses at Surprise Stadium. He observed that “you’re going to see more of the Salt River model, because that was private funding. Public funding is drying up.”

ECONOMIC ENGINE

When the spring-training complexes in Glendale (Dodgers and White Sox, opened 2009) and Goodyear (Indians and Reds, also opened 2009) were designed, adjacent land was set aside for commercial development. The land is still empty.

Not so near Salt River Fields. Bryan Meyers, for the past 17 years the Community Manager of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, said that The Pavilions, a shopping center adjacent to the site, was languishing before the baseball complex was built. “The occupancy was less than 60%, but today it’s over 90% with new pads for stores being added all the time,” and major attractions like iFLY, Topgolf and Butterfly Wonderland have come on board. “Salt River acted as a catalyst to jump-start our economy.”

And the Community’s roaring economy helped pay for the complex. In fact, Meyers points out that it is now “all paid in full. Even the bonds we did were short-term, and they’ve been paid off.” In addition, exhibition games at the stadium provide jobs for Community members, plus it gives vendors the opportunity to sell native foods to fans attending the games.

THREE KEY INGREDIENTS

Salt River Fields wouldn’t have become a reality without three key components.

First, the Diamondbacks and Rockies were permitted to escape their leases in Tucson because there were no other teams for them to play nearby. That allowed their move to the Phoenix area.

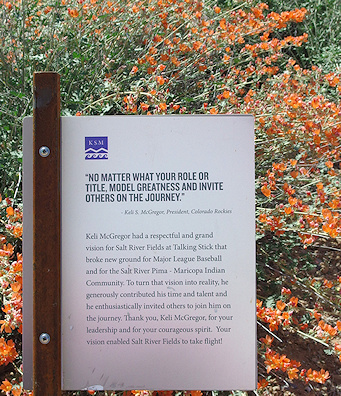

Second, the Rockies’ former President, Keli McGregor, had a profound role in the creation of Salt River Fields. Unfortunately, he died in 2010 before construction was completed.

Hall related how he and McGregor came to develop a bond. “When Keli first started talking about leaving Tucson, I said ‘Let’s do this together.’ After we got a call about a possible partnership with the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community, I picked him up and showed him around.

“I’ll never forget that Keli and I pulled up to this old golf course. Two young guys came running up to get our (golf) clubs, so we said ‘No, we’re not golfing.’ Then we leaned up against our car and looked out and both of us felt chills,” Hall recalls. “We knew this was it. We could envision it all. We each returned to our respective owners and said, ‘We found the spot.’

“It breaks my heart that he never got to see it finished,” Hall added. “I couldn’t be more proud of the brotherhood and bond we created, and the work we did together here.”

Kahn says that while McGregor “saw this project as the opportunity to take our organization to the next level, equally important to him was the partnership aspect. He wanted this to be a success for the Indian Community as much as for the Rockies.”

The Indian Community was so touched by McGregor’s interest in them that they created the Keli McGregor Reflection Trail just outside the main gate of the ballpark (above). The trail contains postings of quotes from McGregor (below right), as well as a lovely, flowing stream, bridges and small sculptures. “They did it on their own as a tangible way to show how they felt about Keli and his impact on the project and on the Indian Community,” Kahn explained.

Which leads us to the third ingredient: the Indian Community itself. Not only did they provide the land and the money to construct the complex, their native culture contributed greatly to the design.

Kahn points out that every year, representatives from the Indian Community meet with the Rockies’ players and staff to describe their history and values. In turn, the team sends players to schools and senior centers at the Indian Community to “continue to build that relationship, to take something out of the ballpark and into the heart of their Community.”

Stein says that it was important “to understand our Native American hosts and their culture and stories, and to reflect that in all that was done. This wasn’t a land deal. This was a culture deal. There is a big difference. We wouldn’t have been able to complete this if we hadn’t understood that.”

Now as fans arrive for exhibition games, they notice the signage along the pathways that describe the Community’s history. They appreciate the plants that are native to the area. They see the colors and architectural styles used by the Community for generations. They can taste native foods at the concession stands. And they hear young people from the Community singing the National Anthem in the O’Odham and Piipaash native languages.

Members of the Community feel the teams and designers were successful in “tastefully integrating our culture into Salt River Fields,” according to Meyers. This was critically important to do. After all, the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community made it possible to revolutionize spring training.

Great article.

Thanks very much. I had so much great material for this piece that couldn’t fit into the print version that I wanted to provide visitors to my site the opportunity to read a full, unedited version.

Well written article. After watching thousands of games at Hi Corbett in Tucson, this place truly is Heaven on Earth!!! Glad others are taking note of the gem

Thanks for the feedback. I think the secret is out about Salt River Fields!

As someone who works at Salt River Fields, this was a great read and one I’m excited to share. Thank you for the great piece!