|

Happy 100th Birthday

I’ve photographed hundreds of ballparks, always in color. At the Rickwood Classic in Birmingham on June 2, 2010, I was tempted to shoot in black and white for the first time.

It wasn’t because there was a lack of colorful scenes. No, there was more color and pageantry than at a college football game. It’s just that this year’s Classic made me feel like I’d traveled in a time machine to 1910. That’s the year that Rick Woodward, the enterprising young owner of the Birmingham Barons, constructed the grandest baseball park in the South. Only the fifth concrete-and-steel baseball stadium ever (the other four had all opened in just the previous 16 months), it was supposed to cost $25,000 to build. But on its opening day on August 18, 1910, the ledger sheet showed that three times as much had been spent. Talk about cost overruns!

Woodward, however, was too excited to dwell on the crushing debt he’d just incurred. He was so overjoyed with the finished product that he donned a Barons uniform and threw out the first pitch. Not a ceremonial first pitch, but the actual first pitch of the opening day game! He wanted to go down in history as the hurler of the first ball (and it was indeed called a ball by the ump) at Rickwood Field. None of the 10,000 in attendance that day could’ve dreamed, though, that 100 years later, thousands would still congregate at Woodward’s sturdy edifice.

|

Rickwood Field is no longer the Barons’ everyday home. The needs of a modern-day baseball team are quite different than what Rickwood can accommodate. There are no luxury suites, no high-res video screens, no Club Level restaurants for well-heeled patrons. No, in 1988, the Barons moved into a modern if somewhat sterile (by comparison) new stadium in the suburb of Hoover, just south of Birmingham.

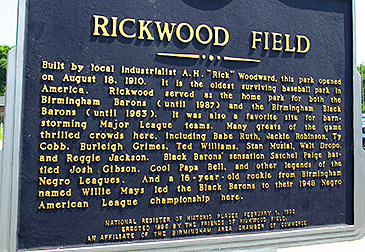

But for one day a year, pro baseball returns to “the oldest surviving baseball park in America,” a designation that comes from the National Register of Historic Places’ plaque in front of the ballpark (above). That game is called the Rickwood Classic, and it’s been held each summer since 1996. The 15th annual affair in 2010, though, was much more than just an opportunity for two Southern League teams to play dress-up in throwback jerseys. No, this year’s event celebrated the 100th anniversary of the ballpark — an event I’ve been looking forward to for years. Indeed, when you consider the history of the “white” Barons in the Southern Association (later Southern League) and the Black Barons of the Negro Leagues, there is no park in the Minors more historic than this one.

Stop and think for a moment about the four concrete-and-steel parks that opened before Rickwood:

The first was Shibe Park (April 12, 1909), which sat where there is now a church just north of downtown Philadelphia (below left);

The second was Forbes Field (June 30, 1909), whose site now holds a street and a classroom building for the University of Pittsburgh (below right);

|

|

Next came League Park in Cleveland (April 21, 1910), where the stadium is almost entirely gone, but where baseball is still played to this day — albeit by youngsters rather than pros (above left);

The fourth was Comiskey Park (July 1, 1910), which was the home of the White Sox for a staggering eight decades … but there’s now a parking lot where the stadium once stood (above right).

What do all four of these have in common? They have all gone the way of the dinosaur, which is why Birmingham’s stadium carries the distinction of being America’s Oldest Ballpark, a designation that is held with a great deal of pride.

|

The original structure that was completed just in time for its August 18, 1910 opening date didn’t have the sprawling roof down both lines like you see at today’s version. It had an exterior much like the one today, and it did have a covered grandstand, but only in the infield. But you don’t have to employ your imagination much at all to get a sense of what it looked like — because today’s facility still has the feel of something many decades old.

Inside the front gates is a lobby area (below left) with souvenir and concession stands, and with a crowd of this size, there wasn’t much room to move. In this area, vendors sold $1 programs and, at the throwback price of a dime, an old-style newspaper about Rickwood Field. Over at the souvenir booth, there were plenty of T-shirts and uni tops with artwork commemorating the 100th birthday of Rickwood. I was a little disappointed, though, that they didn’t produce any commemorative lapel pins for the occasion, because I love collecting such things.

|

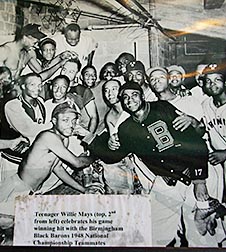

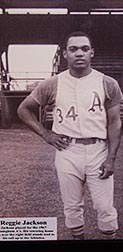

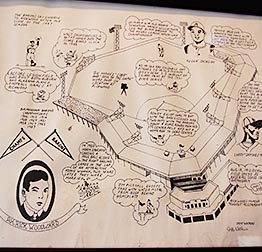

On the walls of this lobby area is a remarkable collection of photos and artwork. A small sampling is shown below. The far left image shows a teenage Willie Mays celebrating with his teammates on the Black Barons, who won the Negro American League Championship in 1948. In the middle is a 21-year-old slugger named Reggie Jackson, who played for the Birmingham A’s in 1967. On the right is an incredible drawing by Jeff Watkins. In it, he depicts notable occurrences at historic Rickwood.

|

As you walk up ramps from the concourse beneath the stands you enter the grandstands, and you realize that Rickwood is unlike any ballpark you’ve ever seen. The immense roof that covers the seating areas is tremendously larger than simple overhangs in ballparks built decades later. That roof, you have to keep telling yourself, is supported with large steel trusses, as this was the first concrete-and-steel ballpark in the South. And, of course, it’s the oldest such park still standing anywhere.

|

|

When the Philadelphia Athletics came to Birmingham to play an exhibition game in March 1910, Rick Woodward had just acquired the Barons. Woodward was eager to show the manager of the Athletics, none other than Connie Mack, where he intended to construct his new ballpark. The story goes that Mack walked around the site, finally telling the Barons’ owner exactly how to lay out the playing field to minimize the effect the afternoon sun would have on the fielders. He also gave Woodward some sound advice on how to keep the seating areas from being baked by the sun as it moved lower toward the horizon in the late afternoon. He suggested putting louvered planks between the bottom of the roof and the last row of the grandstand. By angling those slats, Mack advised, it would keep the sun out but allow air to circulate. You’ll see those louvers to this very day (above right).

|

In the 2010 Classic, the Barons hosted the Tennessee Smokies, and both squads wore replica uniforms from the era of Rickwood’s opening. This added greatly to the century-old feel. I think the modern-day Barons didn’t know quite what to make of their baggy unis (above), but they seemed to enjoy the proceedings immensely.

After all, watching the players out on the field is what this experience is all about. While the grandstand is nothing short of a fantastic place to follow the action, there are two spots that are even more magical. The first is the roof. I spent quite a bit of time up there, because the view of the game and the surrounding light towers (very noteworthy in their own right) is very special indeed. In fact, the shot of the first pitch of the 2010 Classic (below left) was taken in front of the “pressbox” directly behind home plate. By the way, you’ll notice that there is a lot of room between the catcher and the backstop here at Rickwood. That’s the way parks of long ago were designed (their outfield walls were incredibly deep as well, as we’ll see in a minute). The notion of bringing the plate as close to the front row of seats as possible is very much a modern-day concept.

|

The gazebo-like pressbox (you can see it on the roof in the sepia-tone photo that is at the very top of this page) was constructed to closely resemble the one that sat atop the roof when the ballpark made its debut in August of 1910. Photos of Rickwood show the rooftop pressbox was gone by the 1960s, replaced by a much larger — and enclosed — press area at the rear of the grandstand behind home plate. As part of the ongoing restoration of the ballpark, a new rooftop gazebo was constructed in 1997. A plaque within it announces that the structure is dedicated to Chris Fullerton, who was the first Executive Director of the Friends of Rickwood, the organization that to this day is entrusted with the care and maintenance of this treasure of a ballpark.

This very open pressbox (above right), by the way, receives a very pleasant breeze — a breeze that oftentimes blows the reporters’ papers in all directions. This cooling effect is quite lacking in the sweaty stands below, of course. Honestly, I think this gazebo has the nicest vantage point from which to watch a baseball game that I’ve ever seen.

|

The second magical vantage point is, believe it or not, from within the scoreboard. And this isn’t any scoreboard, either. It was built to replicate the manual board of yesteryear. An electronic, exploding scoreboard was erected in the 1980s to replace the old-style model that had been there for decades. The electronic version, thankfully, was scrapped as part of the park’s restoration, and the beautiful hand-operated structure there now (above) is very special indeed.

|

If you’re brave enough to scale the very tall and very steep rungs (on the far right of the lefthand photo above) on the backside of the scoreboard, you’ll get to see where the hard-working folks “hand operate” the thing. As the score changes, and the innings get completed, they slide long, metal slats through openings (above right) to show the fans the numbers in the line score. What does their vantage point allow them to see? That’s in the middle shot above.

When you’re behind the outfield fence examining the workings of the scoreboard, you’ll notice something very striking. There is a monstrous concrete wall that runs roughly parallel to the fence (the shot below left was taken from the scaffolding on the back of the scoreboard, looking down at the area between the older wall and the newer fence). Believe it or not, the concrete embankments were the outfield walls from 1910 until 1937, when the inner fences were erected to make the dimensions more like a ballpark than the Grand Canyon. When those concrete walls were indeed in play, consider that the distance from home plate to the center-field wall was 478 feet.

The “X” that you see on the wall behind the youth baseball players marks the spot where Walt Droppo clobbered a home run for the Barons in 1948. It sailed over the scoreboard and struck the wall at the spot of the “X”. That spot is 467 feet from home plate.

|

Speaking of the outfield fences, today’s Rickwood features vintage-looking ad panels all across the outfield (above right). No, they aren’t leftovers from decades ago. Many were prepared to act as backdrops for movies that were shot here. Indeed, this ballpark has quite a few cinematic credits, including Cobb and Soul of the Game. In 2006, ESPN Classic even televised a re-enactment of a Negro League game here that supposedly occurred in the 1940s.

| The game itself |

| The 2010 Rickwood Classic pitted the hometown Barons against their Southern League rivals, the Tennessee Smokies. A crowd of 9,448 packed the old ballpark, an impressive number for a sweltering day game on a weekday. The fans watched as the home team forced extra innings (I certainly didn’t mind, because I was in no hurry to leave) before falling 8-7 in 11 on a home run by Tennessee’s Marquez Smith. |

My favorite ad panel is directly down the left-field line. It is for the long-out-of-business Woodward Iron Company, the company founded by the father of Barons owner (and builder of Rickwood Field) Rick Woodward. That father, by the way, strongly disapproved of his son’s undying fascination with baseball, believing the frivolous pastime distracted him from serious studies in college and learning enough about the family’s iron business. Anyway, the Iron Company ad can be seen on the left side of the right-hand photo above. Wikipedia reports that descendants of the Woodwards actually sponsored this ad panel.

In addition, the absolutely wonderful book “Bases Loaded with History — The Story of Rickwood Field” tells of an “elderly man of means who never liked baseball,” yet he attended the very first game at the new ballpark in 1910. Author Timothy Whitt tells what happened following the game:

The old gentleman then joined a happily buzzing throng of fans as they exited Rickwood Field … As the old man reached his house on Highland Avenue, he knew that Rick Woodward had done a fine thing, and he resolved to help the young man with his financial difficulties. Baseball must be encouraged; it was a great game — good for the spirit of the people, good for the morale of the working men. The old man decided to purchase the bonds of the ballpark, and retire Rickwood Field’s debt, thereby ensuring Rick Woodward’s success.

That man, of course, was Joseph Hersey Woodward, Rick’s father.

|

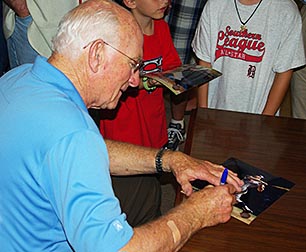

Rickwood Field wasn’t the only star on display at the 2010 Classic, though. The event drew one of the all-time greats of baseball, Harmon Killebrew, and the fans were delighted. As a Minor Leaguer in 1957 and ’58, he played many contests at Rickwood while a member of the Chattanooga Lookouts. The second leading home-run hitter in American League history held court with reporters (above left) near the infield prior to pre-game ceremonies, and then later he patiently signed autographs (for free) for hundreds of fans in an enclosed room off the concourse (above right).

|

The Rickwood Classic, in some respects the greatest day on the ballpark calendar each year, is such a special event that a short article such as this can’t do it justice. Similarly, I can barely scratch the surface relating the historic events that occurred here, such as the incredible 1921 season turned in by Pie Traynor prior to becoming arguably the best third baseman in big-league history; the emergence of a 20-year-old Satchel Paige for the Black Barons in 1927; the exhibitions and barnstorming games starring the greatest talent of the era (Cobb, Hornsby, Alexander, Mathewson, Ruth, DiMaggio, Williams, Musial); 16-year-old Willie Mays, a local kid who grew up a couple of miles from Rickwood, becoming a superstar for the 1948 Black Barons, who won the Negro American League pennant; the sad disbanding of the Barons in 1961 when the team refused the Southern Association’s requirement to integrate the team; the dominant Birmingham A’s of the late ’60’s Southern League, which featured future World Series heroes Reggie Jackson, Rollie Fingers, Bert Campenaris, Sal Bando and Joe Rudi … and then there’s the undisputed greatest game ever played at Rickwood Field.

The game was played on September 16, 1931. The champs of the Texas League that year were the Houston Buffs, who were led by a 20-year-old hurler who struck out an incomprehensible 303 batters while winning 26 games that season. The brash pitcher was Dizzy Dean, and he led the Buffs to Birmingham to face the Southern Association champion Barons in the Dixie Series. If you think there’s a lot of hype for a big sporting event today, you should have seen the fervor that gripped Alabama in the days leading up to the monumental clash. The biggest crowd that had ever attended a sporting event in the state packed Rickwood Field to see the hometown team trot out 43-year-old Ray Caldwell — a boozer who was nine years removed from his Major League career — to face Dean. Read Tim Whitt’s book to learn of the incredible drama that surrounded the 1-0 win by the Barons. Needless to say, anyone there remembered that experience the rest of his life.

|

But that’s what Rickwood Field is: an experience that you’ll never forget. I am very, very thankful that the Barons and the Friends Of Rickwood (please support them, by the way) partner to provide the Rickwood Classic each year. It’s the only way to capture the sense of history that oozes from every crack and crevice in this ballpark. I can’t do it justice with my photos and words here. If you’re even the most casual baseball fan, you need to get to Birmingham, Alabama for a Rickwood Classic at some point in your life. I’ll let you decide whether to bring color film or black-and-white.